John Whitelaw, Jr. was born in Kidder, Mo., one of eight children of Mr. and Mrs. John Whitelaw, Sr., early settlers of the town. He was a farmer, with farms first in his hometown of Kidder, Missouri, and later in eastern Kansas. He and his wife, Bertha Bell, raised three children, one of whom was my father, John Moreland Whitelaw. In his old age he continued to farm on a limited basis; he died in his home at age ninety one. He was part of a dying breed of family farmers, who cultivated grain fields and produce and raised farm animals, with most or all of the labor being done by the family. Like other farmers, he struggled to maintain this way of life during the first half of the twentieth century, when the country was leaving behind small family farms in favor of larger, industrial operations.

His son, John Moreland (my father), recorded memories of his father; here are excerpts:

“My father [John Whitelaw, Jr.] was born in 1870 and educationally, my dad had a kind of a checkered career. I know he probably got through grade school with no difficulty and he went some to Kidder Institute [a local high-school level institution], but I don’t know just how much he went there. But he also enrolled for a period of time as a special student at Drury College where Mother graduated. They may have known each other, but I’m sure they didn’t go out together and there was no courtship at that time. Dad was there about a year. He took mathematics and mechanical drawing. He was always very good in mathematics. He always read a great deal, not only newspaper and farm journals, but he also read books.”

“In the family my dad grew up in, he felt that Will, his oldest brother, had the whip hand over him. One of the episodes that illustrates this is, when Will was 16, 17, and my dad was 14, 15, they got a job to saw up the wood for the school during Christmas vacation, the wood that would be needed to burn the rest of the year. They were using a cross-cut saw; one guy on one end and one on the other end and you just pull it back and forth. My dad, of course, was the younger and the smaller, but he had to hold up his end when he pulled a cross-cut saw. They worked like the dickens.

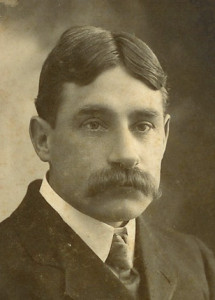

John and his brothers in baseball uniforms. From left to right: John, Will, James, Henry, Kidder, Missouri, about 1895

“When they finally got it done, why Uncle Will, being the older, was the one that went to the school board to get the pay. Of course they didn’t get very much way back then, this is probably about 1885 or 1884. What Will did – he was this sort of a scholarly guy – was he bought the best edition he could find of the Arabian Nights, and it took all the money to buy it. My dad didn’t get any money at all out of the hard work; he got sort of an indication from Will that after Will was finished reading the Arabian Nights, well he could read it if he wanted to. He always felt like he had been shafted on that work project. He didn’t have any say in the decision and all they got out of it was the Arabian Nights. We always laughed about that.

“My parents married in 1903. They moved to a farm in Kansas in March of 1910 from Kidder, Missouri. My father had been in the hardware and implement business in Kidder with his father and with another brother, James. Actually, though, he had had a good deal of experience in farming and worked on farms and, of course, knew a great deal about farm machinery from the implement business, so it was really not a strange venture for him to go to farming in 1910. “

Another reason for the move was that Kidder was in decline as it had been bypassed by the newly built north-south railroad line, which was located about 20 miles west. So John’s father sold the hardware store.

John and Bertha remained on the farm near Lawrence from 1910 to 1919. Their son John Moreland Whitelaw remembered the farm this way:

“I think this was a pretty good farm that Dad had settled on. Wheat was the major crop although we always had corn, oats, alfalfa, Timothy Hay. Dad used to keep as many as eight or ten horses and mules. We often had little colts in the springtime, often little mule colts. The ground was bottom land off the Wakarusa River, and it was called black gumbo. It took a lot of horsepower to plow that land. Mules were pretty good for that. We also kept hogs.

“Dad and mom did a lot of milking on that farm. Dad used to ship whole milk into Kansas City, and every day he would get up and drive the spring wagon with two or three 10 gallon milk cans in it a little over a mile down to the railroad station so it could be picked up on the train and taken into Kansas City.”

The Whitelaws moved to DeSoto in 1919 so the children could attend high school and still live at home; at the farm near Lawrence, they would have had to board in town. On the new farm, John built a house, barn, and various outbuildings.

The family lived there until the start of World War II, when the U.S. military bought their land to build a road connecting a new ammunition plant to the railroad. John and Bertha bought a house in DeSoto and lived there in semi-retirement until their deaths in the early 1960s.

John’s life centered on his farm and his family. He was not a very successful farmer; family farms all across the country were in decline in the early part of the twentieth century, and John did not always make good business decisions. He expressed his concerns in a letter to his sister in Wisconsin:

“We tried to get a better deal out of our milk business but we don’t know how things are coming out yet. The dairies are terribly obstinate – of course in Kansas City they’ve all had it their own way – setting the price – doing the weighing and testing – and we were about to be crowded out of any returns – I sold 3000 lbs of milk the first half of Sept. for $50.00 and the dairies sold it for $182.00 and it looks like the spread was too wide. We may have to hold our milk again before we win our point – but we’ve got to win.” (no date, late 1920s)

I think of my grandfather as a quiet, somewhat passive man. He was not religious, but he was reflective; one of his neighbors told me that my grandfather said he never minded the daily grind of milking; he said it gave him time to think.

He was sentimental about his family, and for years wrote weekly letters to his adult children, all of whom lived far away, covering mainly the weather and crop reports. His children and grandchildren visited sometimes in the summer.

My brother John remembers:

“sitting on the porch with grandpa marveling at how that old man with arthritic hands could swat flies – barehanded – and he never missed. I also remember sitting for hours on the back porch with a .22 rifle trying to nail a gopher that was terrorizing grandpa’s backyard. I shot a lot of shells but never came close.”

My cousin Bill remembers:

“a number of times when I got into trouble – e.g. chasing the chickens, forgetting to latch the gate to the pasture and the cow got out. One time when I was milking the cow, or more accurately trying to milk the cow, I got up from the stool to turn the job over to grandpa and managed to swing my foot over the pail with the milk. A fair amount of straw mixed with manure from the barn floor fell into the milk. Grandma poured the milk through cheesecloth to separate the milk from the manure. I’m not sure what was done with the milk thereafter.”

After visits from his grandchildren, Grandpa liked to leave the furniture undusted, so that their fingerprints on the furniture would remain undisturbed. (When I visited my grandparents’ grave, I left my fingerprints on the granite tombstone in memory.)

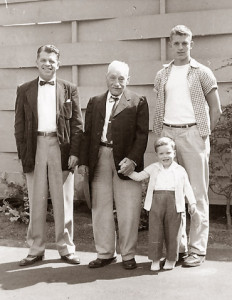

John Whitelaw, Jr. (my grandfather) in the center; to his left, his son John Moreland Whitelaw; to his right, holding his hand, John Whitelaw Rieke (grandson of John Whitelaw Jr.’s brother Henry) and John Moreland Whitelaw, Jr., his grandson. Portland, 1955.

When he retired in his 80s he visited relatives by train. In 1955 he made a long journey to Oregon to visit our family and that of his brother, Henry. However, he was not an experienced traveler. The first night on the train he ordered a large dinner in the dining car and was so shocked at the cost that the next day he got off the train at a stop and bought a bag of hamburgers, which lasted him until he got to Portland two days later. This story appalled my mother, who packed him a hamper for his journey back.

John died in 1961 at his home in DeSoto. His wife, Bertha, saw him through his last years and survived him.

Obituary

“John Whitelaw, 90, DeSoto, died Sunday at the home. He was born in Kidder, Mo., where he once operated a hardware and lumber business. He later lived in Lawrence and moved to DeSoto in 1919.

“He retired from farming several years ago. He was a member of the Plymouth Congregational Church of Lawrence. He was one of eight children of Mr. and Mrs. John Whitelaw, early settlers of Kidder, Mo. He and Mrs. Bertha Whitelaw, who survives, had been married 58 years.“Also surviving are daughter, Mrs. Eleanor Whitford, Mount Hamilton, Calif.; two sons, Neill G. Whitelaw, Clinton, S.C., and John M. Whitelaw, Portland, Ore.; and six grandchildren.

“Funeral services will be at 2 p.m. Wednesday at the DeSoto Methodist Church; burial will be in the DeSoto cemetery. The family prefers no flowers.” (Memorial Obituary)

How you are related to John Whitelaw, Jr.

John Whitelaw, Jr. is on your personal Ancestor Fan. He is the father of John Moreland Whitelaw, and the grandfather of John Moreland Whitelaw Jr., Susan Whitelaw, and Nancy Whitelaw.

Sources

Memorial Obituary, John Whitelaw. The Daily Journal World, Lawrence, Kansas, January 16, 1961.

Whitelaw, John Jr. Letter to Ruth Williams. In: Susan Whitelaw, ed. Dear Sister: Whitelaw Family Letters, 1900-1961 Rocky River, Ohio, 2003.

Whitelaw, John Moreland. Oral History. Recorded 1973, Portland, Oregon.

Whitelaw, Susan. Bertha Bell Whitelaw: A Documentary Biography. Rocky River, Ohio, 2007.