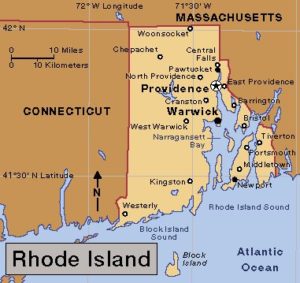

The Love Family Saga tells the story of seven generations of the Love family, from the first immigrants to American shores in the eighteenth century, to those living in the first third of the twentieth century. In Part I of this Saga, I recounted the lives of the first four generations of Loves in America: Generation I: Adam and Mary Love, Generation II: Sgt. Robert and Sarah Love, Generation III: Robert and Susanna Love, and Generation IV: Levi and Eunice Love.

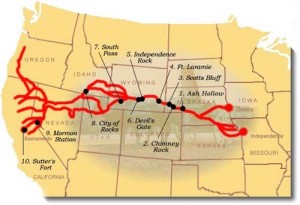

I also identified themes that recur through the generations and connect them. In each generation, some of the children left home and moved to new lands and farms farther west. This migration pattern was not unique to our family, but was part of a larger movement of New Englanders moving westward as lands were appropriated from Native American residents and opened for homesteading.

Another unifying theme concerns the character and personality of many of the Loves: these men were entrepreneurial, bold, and adventurous, but they were not always able to make their big dreams come true. A third pattern involved the wives of these seven generations of Love men: these women came from their own long lines of American settlers and pioneers, and their diverse heritages enrich and expand the Love family story.

Part I of the Love Family Saga, covers the first four generations (click here). Part II carries the Love narrative forward through generations five, six, and seven.

FIFTH GENERATION

Lorenzo (1814-1901) and Lois Hale (1815-1886) Love: From Bridgewater, NY to Newton Township, Michigan

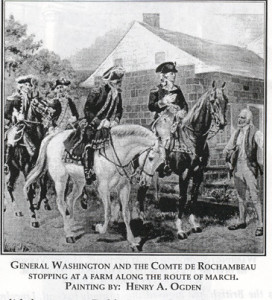

Lorenzo Love was born in Bridgewater, NY, the fourth child of Levi and Eunice Waldo Love. When he was fifteen, he moved with his family to Hartland, NY, where he helped them clear new land for farming. At age 21 he left home and moved fifteen miles away to Yates, NY, where the next year he married Lois Lorain Hale. While there, he raised a company of the state militia and was its captain for three years.

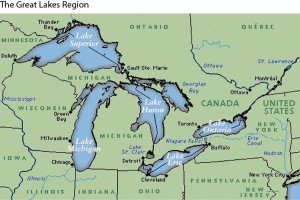

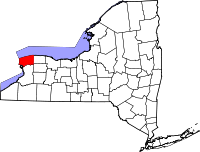

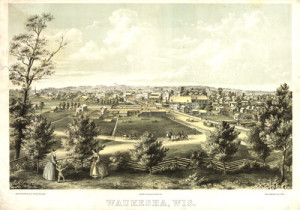

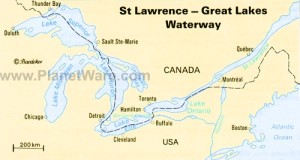

In 1843, Lorenzo, Lois, and their two children, Almon Dwight, age 4, and Lorenzo Homer, age 2, left New York and moved 450 miles west to Calhoun County, located in south-central Michigan. They made this journey just a few months after Lorenzo’s parents, Levi and Eunice Love, also left New York to settle in Waukesha, Wisconsin. Lorenzo’s in-laws, the Hales, left New York as well, and settled near the Loves in Kalamazoo County, Michigan.

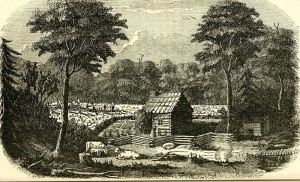

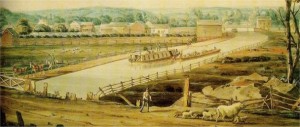

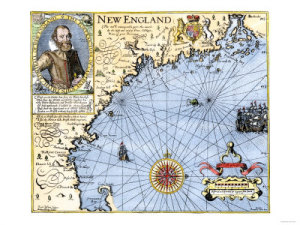

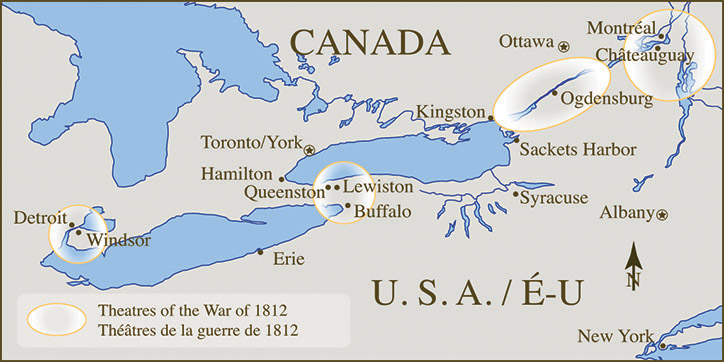

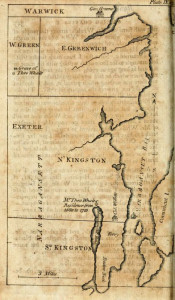

When the Lorenzo Love family arrived in Michigan, it had been a state for six years. Michigan opened for extensive settlement in the aftermath of the War of 1812, when the federal government, in treaties with the local Ojibwa, Ottawa, and Potawatomi tribes, removed them to lands farther west. The Erie Canal provided a route from New England and New York, and thousands of New Englanders moved into the lower third of the state to create homesteads in the Michigan wilderness.

Ceresco: The Grain Company

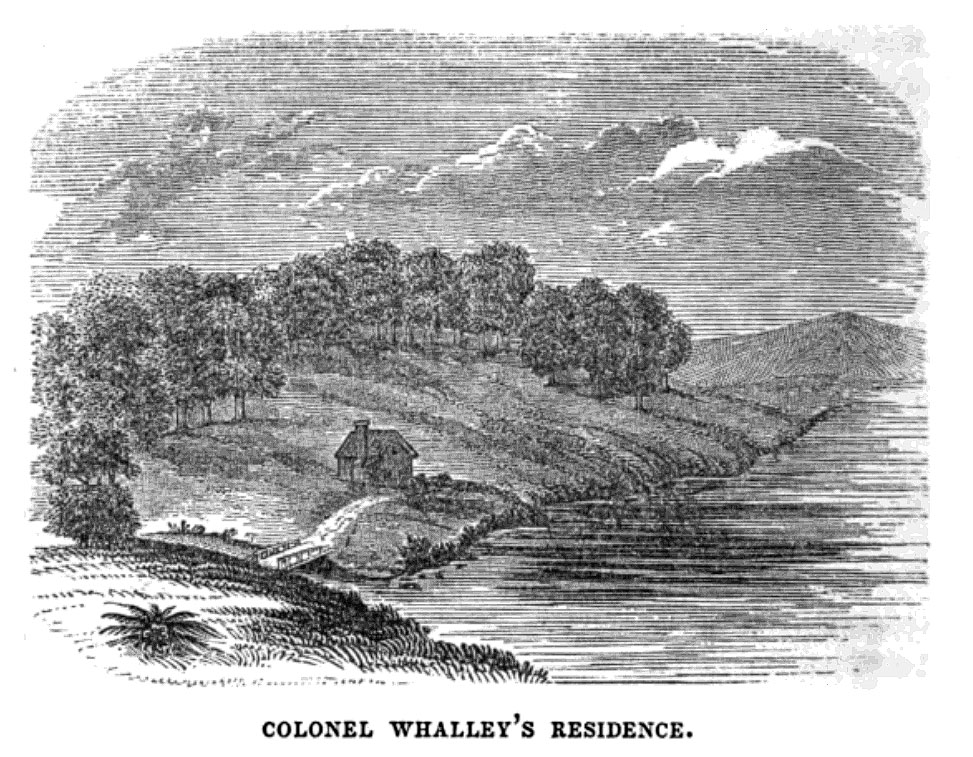

Westwind Mill, Linden, MI, est. 1837. This large mill may have been similar to the five story mill that Lorenzo Love managed in Ceresco, MI, in the 1840s. Photo source: http://www.westwindonline.shoppingcartsplus.com/home.html

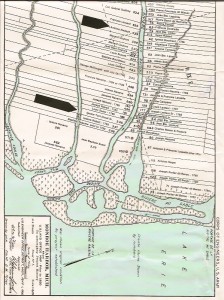

The Loves settled in a town called Ceresco, which its founders named by combining the name of the Greek grain goddess, “Ceres” with the abbreviation for “company”. So the name means Grain Company. Lorenzo took employment at J. Wallingford’s five-story grain mill, located on the Kalamazoo River, and became its general manager. The mill processed grain from a large surrounding region and shipped its products to markets as far away as Chicago and New York.

The region was well-suited for growing cereals; later in the 19th century this agricultural fertility attracted the Kellogg brothers, who established their health sanitarium and breakfast cereal company in nearby Battle Creek. The Loves and their neighboring farmers probably sold wheat and corn to this food-processing company.

The Underground Railroad

The largest monument to the Underground Railroad in the country is located in Battle Creek. It celebrates the role of Harriet Tubman. Like Sojourner Truth, Tubman was an ardent abolitionist, and she is especially remembered for her leadership and bravery in the Underground Railroad. Sculptor: Ed Dwight. The Kellogg Company commissioned the monument in 1993.

In the early 1840’s, about the time that the Love family arrived, Calhoun County became renowned for its fervent support of the Underground Railroad. In one instance, a fugitive slave family had settled there and a group of Kentuckians arrived to return them to slavery. The residents of the County refused to surrender the family to them, and later raised donations to pay a fine imposed on the citizens by a federal court. In 1857, Sojourner Truth, famous African-American abolitionist and women’s rights activist, settled in Battle Creek, the county seat of Calhoun County, because of its strong abolitionist efforts. We have no record of specific involvement of the Love family in the Underground Railroad, but like Lorenzo’s grandparents, Robert and Susanna Love, who attended the church of anti-slavery advocate Rev. Levi Hart, they were embedded in an Abolitionist milieu, and it would have been a pervasive topic and preoccupation.

Descendants of Austin Love, Lorenzo Love’s uncle, in Adrian MI, late 1800s; Photo courtesy of Judy Love

Immigration and Family Separation

After several years working at the mill, Lorenzo bought a farm, and he and Lois became full-time farmers. In addition, Lorenzo served the area at various times as postmaster, clerk, and justice of the peace for the Township. During these years Lorenzo and Lois had two more children, Harriet Lorain, born in 1847, and our ancestor, George, born in 1850.

Lorenzo had one relative in Michigan, his uncle Austin Love. Austin had been raised in Bridgewater, NY and moved to Michigan in 1835. He and his large family lived in Adrian, about 60 miles away from the Lorenzo Loves in Burlington, and it is possible that the families were able to visit occasionally.

Historic Firestone Farm at Greenfield Village, Dearborn, MI, showing an 1876 reaper recently invented to reduce the physical labor of harvesting. Photo source: http://passionforthepast.blogspot.com/2011/08/early-farming-tools-from-days-gone-by.html

However, Lorenzo was separated from his parents and the family he grew up with in Bridgewater. His brothers and sisters were scattered throughout Canada, New York, and Wisconsin. At this time, transportation was difficult, and very few farm families could afford either the time or money to travel long distances for family reunions. Family historian Dorothy McKillop quotes from a letter that Lorenzo, in his old age, wrote to his nephew, Charley Love, in Wisconsin, which expresses the loss he felt at having so little contact with his family.

“As I had not heard of the death of my brother [DeLoss Love] until you informed me, I must say I feel much obliged to you for your kindness toward me. I have never seen DeLoss but once since father [Levi] moved to Wisconsin in 1843. He was then a boy some 16 or 17 years old. I wrote him a letter once but he never answered it. Well, out of a family of 14, only 5 remain.” (McKillop, p. 65)

Lorenzo retired from farming in 1888, after his wife’s death, and lived in the homes of his children until he died in 1901 at age 86. According to his obituary, written by his sons, “ he was an active, vigorous man and was always strictly honorable in his transactions.”

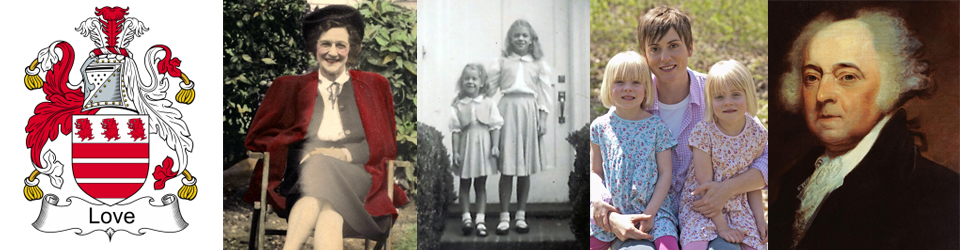

Lois Lorain Hale, Lorenzo’s wife, was descended from New Englanders. Her parents moved from Vermont to Yates County as part of the large migration of New Englanders to western New York after the Revolutionary War, and moved to Michigan in parallel with Lorenzo and Lois in the 1840s. Lois died on the home farm in Burlington in 1886, at the age of 71.

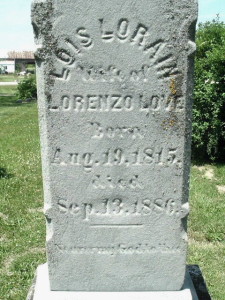

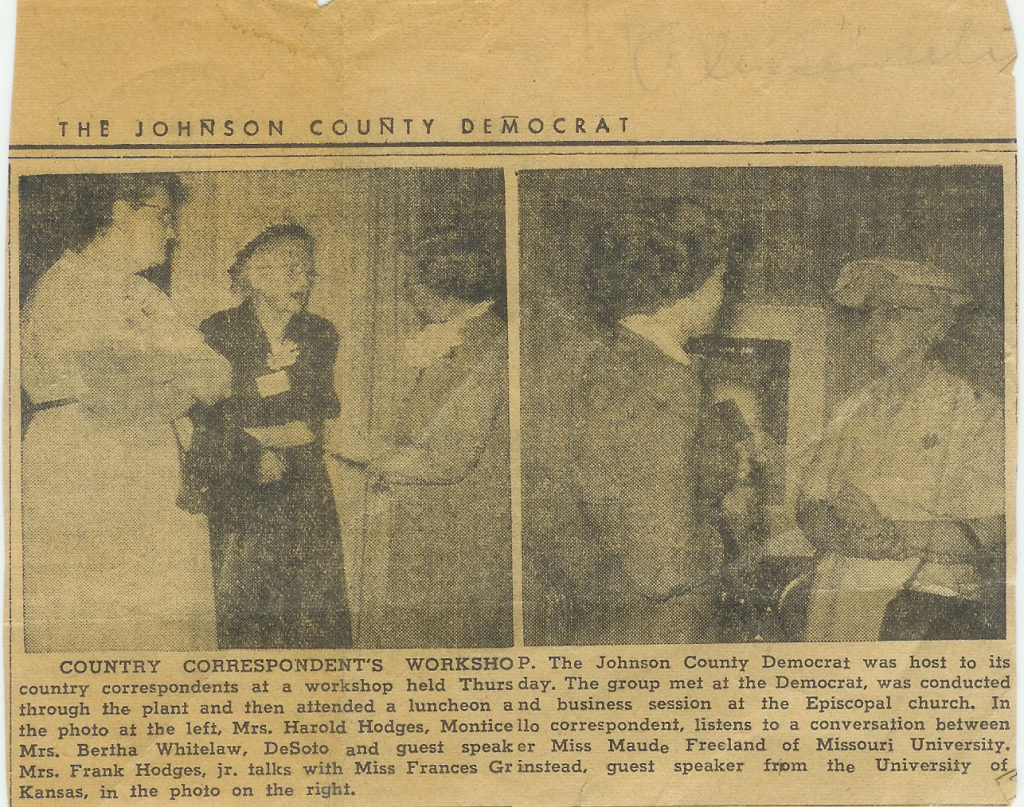

She and Lorenzo lived to see the family begin to move away from rural life into occupations more closely associated with towns and cities. One of their children, Lorenzo Homer, known as L.H. Love, became locally prominent as the publisher of a small-town newspaper, the Athens Times, and George, our direct ancestor, also explored alternatives to traditional rural life (See below.)

Lois and Lorenzo Love are buried at Burlington Cemetery, Burlington, Michigan. The Calhoun County Genealogical Society has recognized Lorenzo Love as a Calhoun County Pioneer (one who settled in the County before 1861) and has officially verified our family’s descent from him and Lois, his wife.

SIXTH GENERATION:

George Winslow (1850-1918) and Hannah Maria Lewis (1854-1946) Love: From Newton Township, Michigan to Livingston, California.

George and Hannah Love Family, 1886, Michigan. Left to right: Ralph, Lewis, George, Charles, Hannah, Olin, Ruth.

George Love was born in Ceresco, Newton Township, Michigan, where his father operated a flour mill. He was the youngest of four children. Soon after his birth, his father left the mill and bought a farm in the area, where George grew up and attended local schools. In 1874, at age 24, he married Hannah Lewis, who lived on a nearby farm, and whom he had probably known since childhood. The couple settled down on farms in Calhoun County and had four sons and a daughter between the years 1876 and 1886: Charles George, b. 1876; Ralph Emerson, b. 1877; Ruth Carrie, b. 1880; Lewis D., b. 1883; and Olin Wayne, b. 1886.

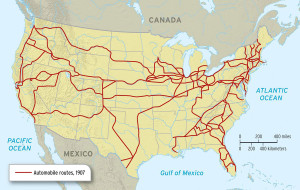

Starting in the 1890s, the Love family and their children made a series of moves that took them from farms to towns, from Michigan to the west coast, and from farming to leadership in farming cooperatives, and to business and professional careers.

Benton Harbor, Michigan

By 1894, the family had moved to Benton Harbor, a town on the shore of Lake Michigan, about 85 miles west of Newton Township. Benton Harbor was a rapidly growing town in the 1890s. The construction of a canal had drained its swamps and also provided a port on the Lake, so that agricultural products could be shipped out to Chicago and other markets. Sawmills, fruit canning companies, manufacturers, and a tourist industry all grew quickly in this late nineteenth century boom town. The 1900 Federal Census lists George Love’s occupation in Benton Harbor as “carpenter,” and it seems likely that he worked on construction projects in this growing municipality. Judging from his later activities on the west coast, he may also have been interested in land speculation.

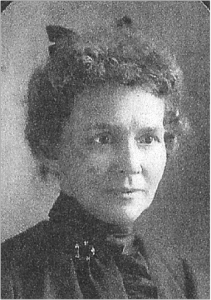

Hannah Love, 1901, age 47, a few years before she left Michigan and moved to Oregon, Source: Fran Bryanton photo archive

Real Estate in Woodburn, Oregon

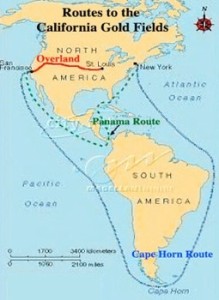

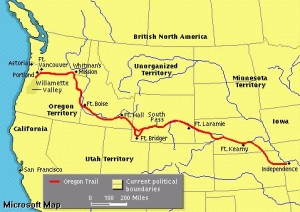

In 1905, George and Hannah, in their early 50’s, and two of their now-adult children (Ralph and Lewis), moved 2,300 miles west to Oregon. They left behind Hannah’s mother, Rachel Freer Lewis, and their oldest child, Charles, and his family. Two of their children remained in the midwest and came to Oregon later. Ruth was a nurse in Chicago; she married Millard Seitz, a lawyer, in 1907, and they moved to Oregon in 1908. Olin was still a teenager when his parents left; he was working in Indiana but joined the family in Oregon a few years later.

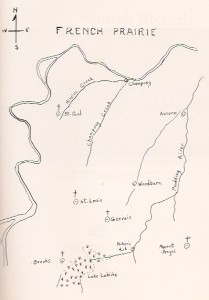

The Love family settled in Woodburn, Oregon, in the heart of the fertile Willamette Valley, a town of about 2,500 people. George and Hannah bought a 50 acre farm, but farming does not seem to have been their primary occupation. George and his sons opened a real estate office, hoping to speculate successfully in the growing demand for the rich farm land in the area.

Both farming and real estate were short-lived ventures, however, and in 1912 George and Hannah moved to Livingston, California, another area of potentially highly productive farm land. George was probably interested in continuing to speculate in real estate, and apparently found the prospects desirable, as the children, Lewis, Ralph, Olin and their families, also left Oregon over the next several years and joined their parents there. Ruth did not move to Livingston. Her husband died of drowning on the Oregon Coast in 1912. She and her young son, William Love Seitz, returned to Chicago where she studied music at the Chicago College of Music. She then established a career as a piano teacher in Anaheim, California.

The California Agricultural Revolution

Family Picnic, July 4, 1914, Livingston, California, two years after the Loves arrived there. Far left, Ralph Love; center, Hannah and George Love; others are Ralph’s wife, Edna McCoy and her relatives. Source: Frances Morton photo archive.

The town of Livingston was named after the famous explorer of Africa, Dr. Livingstone (the final “e” was inadvertently omitted from the application for a post office, so the town name officially became Livingston). Land speculators advertised the area nationally, drawing settlers from as far away as the mid-west. However, as in Oregon, the Love family did not prosper in real estate there, and instead they turned to wheat ranching.

Grain thrasher, Lewis Love ranch, Livingston, California, about 1920. Source: Stan Elems photo archive.

When the Love family arrived, central California was in the midst of an agricultural revolution, and the Loves discovered that wheat farming there was very different from that practiced on their Michigan farm. In California, the farms were called ranches, because the wheat fields were large, flat, nearly empty expanses of land. Scientists developed new strains of wheat compatible with dry farming, so wheat could survive in arid areas. Unlike the small family farms characteristic of Michigan, California ranches replaced intensive human labor with giant farm machinery and large teams of horses, both of which were well adapted to the flat, empty terrain. A single rancher, with the help of hired “hands”, could grow much larger crops than was possible in the mid west. To get a sense of the change in scale, compare the huge harvesting machine shown here with the reaper used by Michigan farmers pictured in the previous section on Lorenzo Love.

The Loves embraced this new method of wheat-growing with enthusiasm. Lewis formed a partnership with a local banker, who provided the capital for them to jointly purchase 1,000 acres, one of the largest ranches in the area. Lewis was in charge of the actual farming. George and Ralph also had ranches. Son Olin joined the family in 1918 and also bought a ranch. My mother, who lived on her father’s ranch for a few years as a child, remembered that her Uncle Ralph, who had lost an arm while working at a saw mill in Oregon, was renowned for managing teams of twelve horses with his one arm. Twelve-horse teams would have been unheard of, and not useful, in Michigan.

“Death to All Rabbits” (Livingston Chronicle, March 9, 1917)

Lewis Love, seated on horse on left, leading a jack rabbit drive, March, 1917. Photo from the Livingston Chronicle, Oct. 12, 1933.

Lewis Love was a popular local figure. Over the years he was elected to be the first director of the Merced Irrigation District, the president of the Livingston farm center, an officer in the Livingston chamber of commerce, and justice of the peace. He was most remembered, however, for being the organizer and leader of a series of massive jack rabbit sweeps. Jack rabbits were so numerous that they seriously threatened the crops. In one sweep, Love organized a thousand men, including contingents from the Japanese, Chinese, and Portuguese communities, for a drive covering ten square miles, with an estimated kill of 6,000 rabbits. (Note: Many thanks to Stan Elems, grandson of Lewis Love, for locating and scanning all newspaper articles in the Livingston Chronicle on the Love family, and for much other help in doing research on the Love family in California.)

George Love died at age 68, in 1918, unfortunately by suicide, after learning from his doctor that his heart was failing. He became despondent, and hanged himself from a rafter in the barn. Although his method of dying was not made public at the time, I have chosen to do so here because currently we understand suicide to be a symptom of depression, which, like many other mental and physical disorders, can have a physiological base. It is useful for those in the Love line to know if they might have a genetic susceptibility to depression.

Hannah Lewis Love survived her husband by many years. She lived to see the end of World War II. During her widowhood, Hannah divided her time between Livingston and Los Angeles, at the home of her daughter, Ruth. She returned to Michigan once that we know of, in 1918, to visit her mother, then in her 90s, and her son Charles and his nine children. Hannah died in 1946 at the age of 92 and is buried next to her husband in Turlock Cemetery, near Livingston.

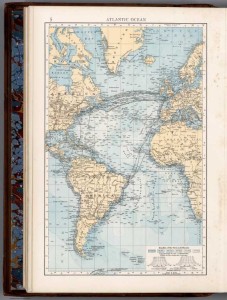

Hannah’s ancestry includes very early immigrants to America. Her mother was Rachel Freer. Rachel was born in New Paltz, NY, the home base of the extensive Freer family, who were Huguenots fleeing persecution in France. Through her father, Adna Lewis, Hannah was a descendant of Thomas Lewis, an early settler to Dutch New York, and by his marriage, to several of the early Dutch families there. Click here. Through her paternal grandmother, Hulda Nye Lewis, Hannah was also related to the Nyes and other Puritan settlers of the Cape Cod town of Saugus in the 1600s. Click here.

Hannah Love’s loveseat, which she brought from Michigan to California, now in the Historical Museum, Livingston, CA. Photo Susan Whitelaw, 2009.

George and Hannah’s children continued the trend that began a generation earlier of transitioning from farming to urban occupations. Charles was a musician and piano tuner in Michigan his entire adult life. His expertise was recognized by opera singer Helen Traubel, who always insisted that he tune the pianos that would accompany her performances in the area. Lewis left ranching after several years to become a justice of the peace in Livingston. Ruth had obtained professional education in two fields: music education and nursing, and, as a single mother, was able to support herself and her son in these professions. Olin tried a number of occupations and was a farmer only briefly (see below).

Charles Love, tuning a piano at the Grinnell Brothers Music Store, Lansing, MI., probably the 1920s. Source: Courtesy Lori Love Smith.

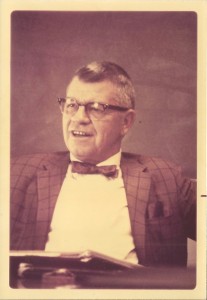

Lewis Love, Justice of the Peace, in his courtroom, Livingston, CA, 1933. Source: Stan Elems photo archive.

GENERATION SEVEN

Olin (1886-1930) and Mabel Goulet (1889-1963) Love: From Newton Township, Michigan to Portland, Oregon

Olin Love was born in 1886 in Burlington, Michigan. According to his daughter, Alvis, he was originally named Leland Stanford Love, after the railroad industrialist, but the name was changed to Olin Wayne when he was five or six, for reasons that are now obscure. “Wayne” may be a reference to “Mad Anthony Wayne,” a military leader of the Revolutionary War, who later helped win Michigan and the Northwest Territory from Indian and British influence.

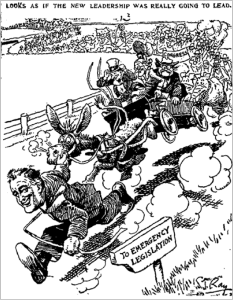

Olin was the youngest of five children born to George and Hannah Love, and spent his earliest years on their farm in Burlington, Michigan. During his childhood the family moved to Benton Harbor, on the coast of Lake Michigan. This was the first of many moves that were to characterize his peripatetic life. A 1912 book of biographical sketches of self-made men in Oregon details Olin’s restless energy. At the time the book was written, Olin was 26 years old. He and others like him took advantage of the opportunities open to ambitious young men attempting to leave the farms homesteaded by their ancestors and move into the modern world.

Early 20th century cigar sign, Spokane, Washington. Photo by Larry Mann. Source: http://www.narhist.ewu.edu/pnf/articles/s1/iii-2-3a/historical_signs/historicalsigns.html

“[In Benton Harbor, Michigan] he pursued his education in the common schools until he had attained the age of thirteen years. He then laid aside his textbooks and apprenticed himself to the cigar maker’s trade, which he followed in twenty-six different states. He subsequently located in Elkhart, Indiana, engaging in business there until 1908. In February of that year he disposed of his establishment and joined his father, who had previously purchased a ranch of fifty acres near Woodburn [Oregon]. Soon thereafter he went to Spokane, Washington, where he followed the cigar business for a year, but at the end of that time he returned to Woodburn and together with his brother Louis D. opened a real-estate office. Although they have been engaged in this business for only a brief period, they have become very well established and have every reason to feel most sanguine regarding its future success.” (Joseph Gaston, 1912)

Olin Love married Mabel Goulet of Woodburn in October, 1910; their daughter Alvis (my mother) was born a year later. The family moved to San Diego in 1917, but then moved to a ranch in Livingston, California, in the San Joaquin Valley, joining Olin’s parents and siblings. During this time, Olin became interested in organizing farmers and was involved with California’s Farm Bureau.

Traveling Salesman

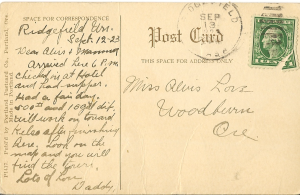

In 1921, Mabel’s poor health caused the family to move back to Woodburn, where they could be near Mabel’s parents. Olin took a position as a salesman for a firm producing food supplements for livestock, the Economy Hog & Cattle Powder Company. This large Iowa company distributed its products nationwide. Olin, as company sales representative in the Northwest, traveled continuously through Oregon and Washington.

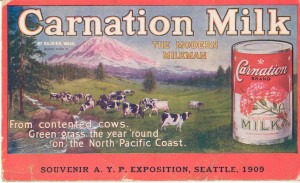

He was recognized as a top salesman for the Company in 1928 and 1929, and was described in the firm’s newsletter of July, 1930, as “one of the most energetic, as well as capable salesmen ever to represent the Economy Company.” The May, 1930, edition of the newsletter reported that: “Mr. Love had the faculty of being able to approach big men with large business firms. He was the man more responsible than anyone else in getting the business from the Carnation Milk People,” a large dairy farm operation with over 1,000 head of Holstein cows.

Olin (far left) and Mabel (seated under the awning) on their boat with friends, Willamette River, 1929

The family moved to Portland in 1925, so Alvis could attend a Portland high school. Olin was determined that she would have a good education and attend college, a somewhat unusual ambition to have for a daughter at that time. During these Portland years, Olin became owner of a boat with which he entertained his family and his clients for the Economy Company on fishing trips along the Columbia and Willamette Rivers. A fellow salesman wrote in the company newsletter (May, 1930) that he “had the pleasure of riding with Mr. Love in his house-boat on the Willamette and Columbia Rivers of Oregon. Mr. Love was a splendid entertainer and host. . . . [He] loved to fish, hunt; he enjoyed out-door life and was especially fond of being on the water.”

Olin Love died unexpectedly and prematurely of complications from surgery on duodenal ulcers in 1930 when he was in his early 40’s. Unfortunately, he died just as he was becoming financially successful, and had not had time to provide for his wife and

daughter. This was before the days of Social Security, so his death caused both his wife and daughter to struggle financially. His daughter, Alvis, remembered him as a kind and devoted father, but one who was a rolling stone, always eager to try a new job or see a new part of the country. During his lifetime, he lived in numerous states and tried many different occupations. The ones he seemed to like the best involved constant travel.

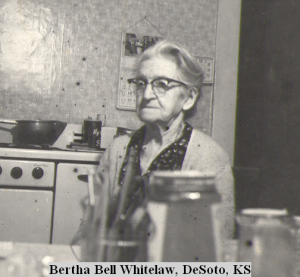

Mabel Love outlived her husband for many years, supporting herself as an apartment house manager. I have written about her here. Her mother, Florence Beach, was the daughter of Amos Beach, Civil War Veteran (click here). Her father was W.H. Goulet, son of French Canadian pioneers S.A. and Marcellisse Goulet (click here). Olin and Mabel’s daughter, Alvis Love Whitelaw, (my mother) continued the family trend of moving from farming to an urban way of life. She obtained a college degree in 1933 and had a career in social service. I have written about her here.

Endings and Beginnings

Roger Schartzer (grandson of Charles Love) center, with parents Ruth and Vernal Schartzer on right, swearing-in ceremony as Chief Warrant Officer of Coast Guard, 1979, Phoenix, AZ. Photo courtesy Roger Schartzer.

The death of Olin Love in 1930 marked the 200th anniversary of the arrival of Adam and Mary Love in America in 1730. As the generations progressed through these two centuries, some patterns gradually ended. The movement westward came to a stop, as the descendants of George and Hannah Love ran out of land on the shores of the Pacific Ocean; instead, they moved north and south, up and down the coast from Washington and Oregon to California and back again. The pattern of small scale family farming as the normative occupation for Love families also ended, as it did for the country as a whole.

Fran Bryanton, retired auto worker, and daughter of Charles Lov. Photo taken on her 90th birthday, singing with her nephew, Bill Love, Lakeland, FL, 2008

The sixth and seventh generations ushered in new ways of life, with a growing urban orientation. The Loves took advantage of windows of opportunity to move out of agriculture to pursue occupations and careers, for example, by working for agricultural industries or taking leadership in farm organizations. Their big dreams didn’t always work out, but their willingness to take risks and their sense of adventure helped these families to see and profit from opportunities in towns and cities.

Hazel Love (Lewis Love’s daughter), fourth from right, and Alvis Love, (Olin Love’s daughter), third from right, Jordan-Atwater School, Livingston, CA, about 1918.

The lives of the great-grandchildren of George and Hannah Love reveal another emerging trend, the increasing importance of education. Among their descendants are Ph.D’s, college professors, and physicians. This trend occurred for women in the family as well as men, as the girls in these families were likely to receive as much or more education than the boys.

Nancy Whitelaw, Ph.D. and Vice President, National Council on Aging, Olin Love’s granddaughter; with Evie and Stan Elems, M.S., biology professor, and grandson of Lewis Love. Photo by Susan Love Whitelaw, Livingston CA Historical Society, 2009

The photos that appear throughout this post of George and Hannah Love’s descendants are intended to suggest the wide range of occupations they found as they adapted to life in urban, industrial America. The children and grandchildren of George and Hannah Love forged pathways for themselves in many fields, including music, the ministry, public administration, social service, sales, health care, manufacturing, the military, and small businesses.

References for Lorenzo and Lois Love

Underground Railroad Monument, at http://michiganhistory.leadr.msu.edu/battle-creek-and-the-underground-railroad/things-to-see-in-battle-creek/; Ceresco, at www.Wikipedia.org; Rosenstreter, Roger L. (1980) “Calhoun County” Michigan History, Vo. 64, no. 3, p. 7-10; Calhoun County Genealogical Society, Pioneer Certificate for ancestor Lorenzo Love, Marshall, MI; U.S. Federal Census 1840, Orleans County NY; U.S. Federal Census, 1850, 1860, 1870, 1880, Calhoun County, MI; History of Calhoun County Michigan (1877), Philadelphia: L.H. Everts & Co., p. 174; Newton Township, (1873) Atlas of Calhoun Co. Michigan, New York: F.W. Beers, p. 57; Love, L.H. & G.W. (1901) Death of Lorenzo Love, The Athens Times, Athens, Calhoun Co. Michigan, August 3, p. 1. ; Lorenzo Love and Lois Love Gravestones, Burlington Cemetery, Burlington, MI; Berrien, Michigan death certificate (1901), Lorenzo Love; McKillop, Dorothy & Love, Mary Anne, eds. (1991) Love Family HIstory, MS and DVD/CD Rom reprint, Seattle, WA, p.. 76.; Waldo LIncoln (1902) Genealogy of the Waldo Family, Worcester, MA: Press of Charles Hamilton, p. 490. Sources for Hale family, all on Ancestry.com: Vermont Vital Records, Benjamin Hale, born 4 Marcy, 1787; Findagrave Benjamin Hale, died Jan. 1866, Mountain Home Cemetery, Kalamazoo, MI; 1830 U.S. Census, Royalton, Niagara, NY,Benjamin Hale; 1840 U.S. Census, Yates, Orleans, NY, Benjamin Hale; 1850 U.S. Census Index, Portage, Kalamazoo County, MI, Benjamin Hale; 1860 U.S. Census, Oshtemo, Kalamazoo County, MI, William Hale (mistake for Benjamin Hale?).

References for George and Hannah Love

1860, 1880 U.S. Census, Newton, Calhoun, Michigan; 1900 U.S. Census, Benton Harbor, Michigan; 1910 U.S. Census, Woodburn, Oregon; Death of Lorenzo Love, The Athens Times, Athens, Calhoun Co., Michigan, August 3, p. 1; City of Benton Harbor – History, available online at http://bentonharborcity.com/history/; Gaston, Joseph (1912). Olin Wayne Love. Centennial History of Oregon, 1811-1912, Volume III; Biographical Sketches, Clarke Publishing Co., Chicago, 1912, pp. 546-547; Olmstead, Alan L. and Rhode, Paul W. The Evolution of California Agriculture, In California Agriculture: Dimensions and Issues, p. 1-28, Giannini Foundation, 2011, available online at http://www.giannini.ucop.edu/CalAgbook/htm; G.W. Love Dies at his Turlock Home, Aged 64. Livingston, CA, Livingston Chronicle, Feb. 22, 1918; Death Certificate, George Winslow Love, 1918, Stanislaus County, CA; Marriage Record, certified: Love-Lewis, State of Michigan, County of Calhoun, December 1, 1874; Whitelaw, Alvis, Oral History, Recorded by Susan Whitelaw, Oregon and Michigan, from 1990-1996; Stanislaus County, CA, Death Certificate for George Love (1918); Los Angeles County, CA, Death Certificate, Hanna M. Love (1946); Death Comes Peacefully to Judge L.D. Love, True Friend, Community Leader, The Livingston Chronicle, October 12, 1933, p. 1; Calhoun County, MI Death Certificate, Rachel (Freer) Lewis, 1920.

References for Olin and Mabel Love

Gaston, Joseph (1912). Olin Wayne Love. Centennial History of Oregon, 1811-1912, Volume III: Biographical Sketches. Clarke Publishing Co., Chicago, 1912. pp. 546-547; Love Buys Home Ranch (October 24, 1919), The Livingston Chronicle, Livingston, California; O.W. Love. (May, 1930) The Livestock Reflector, a publication of the Economy Hog & Cattle Powder Co., Shenandoah, Iowa. Vol. II, No. 1. p. 16 and p. 31; O.W. Love Succumbs (March 20, 1930). The Woodburn Independent, Woodburn, Oregon, p. 1.; State of Oregon, Center for Health Statistics. Certificate of Death, Orin W. Love. (Note typo on certificate: Orin instead of Olin). March 14, 1930, Portland, Multnomah, Oregon.; State of Oregon, Center for Health Statistics. Certificate of Marriage, Olin Wayne Love and Mabel Clara Goulet, Oct. 26, 1910, Woodburn, Marion, Oregon; U.S. Federal Census. (1900). Ollin W. Love. Benton Harbor, Berrien County, Michigan; Whitelaw, Alvis. Oral History. Recorded by her daughter, Susan Whitelaw, from 1990 to 1996, in Oregon and Michigan.