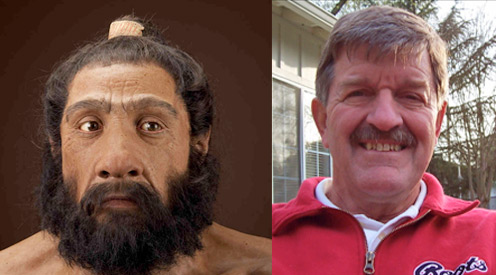

Recently, my brother, John Moreland Whitelaw, Jr., had his DNA analyzed by the genetic testing company, 23 and Me. I wrote earlier about one finding concerning our Neanderthal heritage (click here).

The three men are John Moreland Whitelaw (1911-1974), his father John Whitelaw, Jr. (1870-1961), and John Moreland Whitelaw, Jr. (1939-). All three carry the Whitelaw Y-chromosome DNA. In front is John Whitelaw Rieke (1953-), whose mother was a Whitelaw. He does not carry the Y-chromosome DNA because it only passes from father to son, but, like all the Whitelaw family, he has inherited Whitelaw genes in other parts of his DNA. Picture taken in Portland, Oregon, 1955.

The analysis also revealed our family’s deep past through examination of John’s Y-chromosome DNA. Y-chromosome DNA is passed down from father to son over generations. The analysis places our family in a “haplogroup,” which, according to the 23 and Me website:

“is a family of y-chromosomes that all trace back to a single mutation at a specific place and time. By looking at the geographic distribution of these related lineages, we learn how our ancient male ancestors migrated throughout the world. “

This DNA information supplements and extends the information we have from family records. In this article, I will first trace our Whitelaw family back in time using written records, and then explore how the DNA analysis allows us to go back further to place the Whitelaws in history and even pre-history.

Our History from Written Records

Our written records on the Whitelaw family extend back to James Whitelaw. From his death certificate we know that he was born in 1784-85, in Ayrshire, Scotland, and died in 1866 in Glasgow. He was a cotton weaver by trade. He and his wife, Jane Turnbull, had two daughters and five sons, including our direct ancestor, William Whitelaw, who immigrated to the U.S. in 1856.

The written record takes us back a little further. From James Whitelaw’s death certificate we know that his father’s name was William Whitelaw. We can assume that William was born sometime around 1750, since he had a son born in 1785.

We can even go back a little further. One of James’s two sons who immigrated to the U.S. was Robert Whitelaw (1819-1918), brother to our direct ancestor, William Whitelaw (1807-1887). In a newspaper interview Robert said that he could:

“trace his ancestry to the time of the covenanters in Scotland when all but one of the four Whitelaw brothers were killed at Bothwell Bridge and the estates confiscated by the crown.” (Milestone, 1916.)

The Covenanters were Scots Presbyterians who fought the Scottish government and the English crown over religion. The Battle of Bothwell Bridge, near Glasgow, occurred in 1679. The Covenanters lost the battle to Scottish royalist forces, and many were killed or taken prisoner. If Robert Whitelaw’s memory of ancestral involvement in the Battle of Bothwell Bridge is substantially correct, we can place Whitelaw ancestors in the Ayrshire and Lanarkshire regions of Scotland as far back as the seventeenth century.

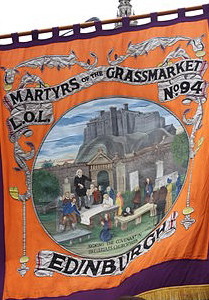

An interesting side note: one notable person in this battle was a John Whitelaw, known as the Monklands Martyr. He was taken prisoner, tried and hanged along with other Covenenters at the Grassmarket area of Edinburgh. A transcript of his trial still exists.

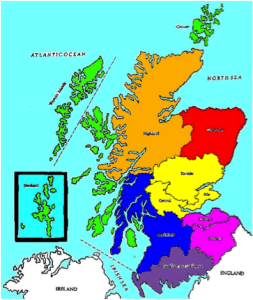

Map of Scotland. The Ayrshire-Lanarkshire region is dark blue. This area was historically called Strathclyde.

The Whitelaw surname is found mainly in the central and southern regions of Scotland and in northern England. The name means “White hill” and was probably adopted by various families who resided near a hilly area. So the name by itself does not necessarily imply a family connection, and so far I have not found a family link to the Monklands Martyr.

In summary, the written record places the Whitelaws in southwestern Scotland, in the regions of Lanarkshire and Ayrshire, from as far back as the 1600s. This area was historically called Strathclyde, and is shown as the dark blue region on the map at right.

Our Scottish DNA

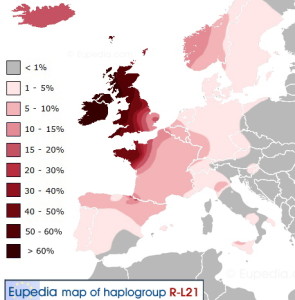

Map showing the major haplogroups of Europe. The red areas, which include Western Europe and the British Isles, are dominated by R1b.

John’s y-chromosome DNA analysis reveals the major “haplogroup” to which we belong and also a series of ever smaller sub-haplogroups created over millenia by a subsequent, intermittent process of gene mutation. At a general level, John’s DNA places us in the haplogroup R1b, the most common haplogroup in Western Europe today. R1b had its origins in southwestern Asia and spread to Europe in pre-historic times. Science has not yet been able to definitively determine the timing and process by which people of this haplogroup settled Europe. (Busby, 2011).

Map showing distribution of L-21. It shows that over 60% of men in the western areas of the British Isles carry this genetic marker.

The Whitelaws are also part of a smaller sub-haplogroup L21 (also known as S145 and M529), created by a series of gene mutations subsequent to the creation of R1b. This sub-group is very common in the British Isles, particularly in the western areas, including Ireland, Wales, and the west of Scotland. According to Scottish geneticists Alistair Moffat and James F. Wilson, the L21 marker:

“probably originated in southern France and northern Iberia [Spain] and people carrying it came to Ireland and western Scotland. This was not a wave of migration but a series of small movements over time, probably in the millennium between 2,500 BC and 1,500 BC.” (p. 89).

The combination of the written record and the DNA evidence supports the conclusion that the Whitelaw family’s origins are in Scotland. They may have arrived in the British Isles around 4,000 years before the present time. At some point they settled in the southern area of Scotland historically known as Strathclyde, probably living as small homesteaders, sheep herders, and weavers. There we find them when the written record of their existence begins in the 17th century.

We Are Celts

The Whitelaw DNA places us squarely in the ethnic, linguistic, and cultural grouping known as Celts. According to Moffat and Wilson (p. 158), scientists have characterized the S145 marker (also known as L21) as the quintessential marker of Celtic language speakers on both sides of the Irish Sea, including Ireland, western England and Wales, and western Scotland.

Celtic people are generally thought to include members of clans and tribes who inhabited Europe in ancient times. These people had a distinctive, highly decorative style of art, characterized by flowing, sinuous lines, and stylized animals and human faces. Their religion was Druidism. They lived as small

The Gathering of the Whitelaw Clan, Oysterville, Washington, 2006. Everyone in the picture was descended from John (1835-1913) and Mary Neill Whitelaw. The t-shirt colors signify descent from three of their children.

homestead farmers and herders in family groups. Both men and women adorned their bodies with tattoos. They were fierce and brave warriors, but, after a long series of battles around 2,000 years ago, they were finally defeated by the Roman army’s superior organization and engineering skills. Today, Celtic traditions live on in the survival of Celtic languages in Ireland, Scotland and Wales, and in popular culture, such as music, handicrafts, spirituality that connects to nature and the seasons, and Renaissance fairs.

References

Busby, George B.J. et al. (2012) The peopling of Europe and the cautionary tale of Y chromosome lineage R-M269.” Proceedings of the Royal Society B. , 279, 884-892. First published online 24 August 2011.

James, Simon. (1993) The World of the Celts. London: Thames & Hudson.

Moffat, Alistair, and James F. Wilson. (2011). The Scots: A genetic journey. Edinburgh: Berlinn Limited.

“Milestone of Life: The Remarkable Vitality Shown by Robert Whitelaw”, published in 1916. No name of the newspaper on the clipping I have, but it was probably the local Portage, Wisconsin paper.)

Sykes, Bryan. (2006) Blood of the Isles. London: Random House.

Wikipedia. Haplogroup R1b (Y-DNA).

For More Information

Click here for a complete copy of: The Life of John Whitelaw (1835-1913), A Documentary Biography with an Appendix of Whitelaw Family Documents, by Susan Love Whitelaw, 2006.

Click here for a complete copy of: The Life of Mary Neill Whitelaw (1840-1925), A Documentary Biography with an Appendix of Neill Family Documents, by Susan Love Whitelaw, 2004. Note: Mary does not carry the Whitelaw DNA, but was married to John Whitelaw and is an ancestor of many Whitelaws living today.