Our French-Canadian ancestors were adventurous travelers. Their journeys across North America were dangerous and difficult. Yet, they were also a quiet, self-effacing people who have left little personal record of their lives, and they have faded into history, largely forgotten. In this they resemble the narrative of French-Canadians generally in this country. French-Canadians were French speaking Catholics, and were among the first Europeans to explore widely the vast wilderness of North America. Although farming was always a component of French-Canadian life, as “voyageurs” they also traveled the rivers and Native American trails in pursuit of beaver and other animal skins for the lucrative European fur trade. They trapped and also traded extensively with Native Americans, then sold the furs to European companies. As the fur trade declined in the 19th century, French-Canadians gradually settled down to farming and businesses, and before long they had blended in with their American neighbors. Today, French-Canadian heritage societies and the many French place names across the country remind us of the important French-Canadian influence on the early history of this country.

The Duvals and Nadeaus

Our family’s French-Canadian story starts with the 17th century migration of French peasants from the Paris area and other parts of France, to the lands bordering both sides of the St. Lawrence River in what is now Quebec, Canada. Our ancestors the Goulet, Nadeau and Duval families were among these immigrants to the New World.

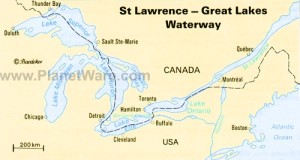

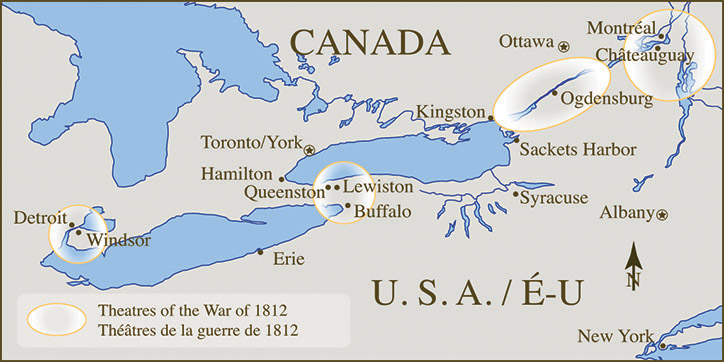

After several generations of farming and trapping in Quebec, the Nadeaus and Duvals joined the stream of French-Canadian migrants who traveled down the St. Lawrence River, through Lakes Ontario and Lake Erie, and up the Detroit River to Detroit. The French government had established Fort Detroit in the early 1700s to solidify the French claim to the Great Lakes area and to counteract British encroachment there. They offered free land and farming supplies to French-Canadians willing to come. At the time the Duvals and Nadeaus arrived, in the 1780s, the city was officially part of the United States, but the population of Detroit was still predominantly French (DuLong, 2001).

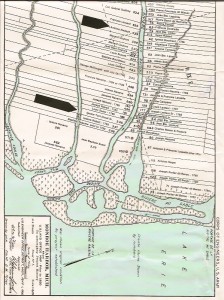

Riviere aux Raisins

Map of Monroe, MI ribbon farms, including those of Marcellisse’s grandparents. The upper black arrow shows Antoine Nadeau’s 539 acre farm; the lower black arrow shows Ignace Tuot Duval Sr.’s 346 acre farm. Original map located at the Monroe Historical Society.

The French Canadian immigrants settled all along the Detroit River, and the Duval and Nadeau families soon moved south from Detroit to the Riviere aux Raisins (named for the wild grapes on its banks), an area then called Frenchtown, now Monroe, Michigan. Like their fellow immigrants, they established “ribbon farms,” a settlement pattern in which homesteads had a narrow frontage on a river and then, in a long, narrow ribbon, went inland until they ended in an indefinite border in the wilderness. This pattern allowed the settlers to use the river for transportation, fur trapping, and a source of food to supplement the produce from their farms. During these early years of the 19th century, the French were the predominant ethnic group in this area. They trapped, traded, and farmed, maintained good relations with their Native American neighbors and fur trading partners, and tried to stay out of the conflicts among Britain, the United States and Native American confederations over control of the Great Lakes territory. (For more on the War of 1812 in Monroe, Michigan, and the role of French-Canadians living there, click here.)

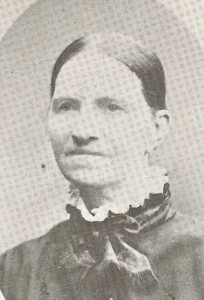

Marcellisse (Duval) Goulet (1822-1911)

Marcellisse Duval Goulet in younger years. (from Munnick, St. Louis Church Records, vol. II, courtesy Louise Manning Giles)

Our ancestor Marcellisse Duval was born on such a farm in 1822, to Michael and Agatha (Nadeau) Duval, and was baptized in the Catholic Church. French-Canadians tended to have very large families, and Marcellisse was the third of ten children. She grew up to marry a new-comer to the French-Canadian settlement in Frenchtown, Samuel Goulet. He and Marcellisse led remarkable lives, but left no personal records. In recounting their stories, I have relied on their Obituaries, written by close relatives, public records, and the memories of their great grand daughter, who was my mother. These sources are listed at the end of this essay.

Samuel Antoine Goulet (1816-1906)

Samuel Goulet was born in Montreal, Canada in 1816 to Pierre and Marie Goulet (Munnick, 1981). He received a good education there, and then, when he was about 17 years old, he migrated to Monroe, Michigan. He probably traveled the usual route of French-Canadians, down the St. Lawrence River and through Lake Ontario and Lake Erie. At the time he arrived, Monroe was a growing agricultural center. It was a hub for newcomers from the East arriving in Michigan territory via the Erie Canal, and heading to the interior to homestead. A few years after Samuel arrived, in 1837, Michigan became a State. Samuel, a carpenter by trade, also worked on the newly developing local railroad system. In 1842, at about age 26, he married Marcellisse, then age 20, at St. Mary’s Catholic Church, in Monroe.

California Gold Mines

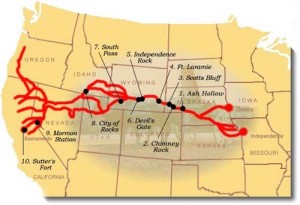

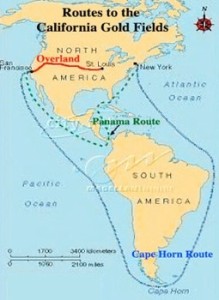

In 1852, after living in Monroe for 19 years, Samuel and two of his brothers headed west to California, lured by stories of the Gold Rush. Marcellisse remained in Monroe and worked as a school teacher to support the couple’s three children. The Goulet brothers took a cross country route with a contingent of horses they planned to sell to the gold miners. Samuel is listed in the 1852 California Census as a resident of Calaveras County, where gold had been discovered in 1848.

“Land-Looking” in Oregon

He remained there only briefly; by April of 1853 he was in Marion County, Oregon, registering a land claim. It is likely that getting a foothold in the fertile Willamette Valley of Oregon, recently opened for homesteading by the territorial Oregon government, had been the plan all along. Samuel remained in Marion County, Oregon for two years and was on the tax rolls there. We don’t know why he stayed so long. One source says he spent his time in the west mining and “land-looking.” Perhaps he needed to build a house or make other improvements in order to validate a successful claim. He may also have been working to save money for the return trip home.

Sailing Around the Horn

The clipper ship Northern Light on which Samuel Goulet traveled around Cape Horn in 1855 (Google images)

Samuel left the West coast sometime in mid 1855. He made the return journey coming around Cape Horn, at the southern tip of South America, on the clipper ship Northern Light, made famous by sailing from San Francisco to Boston in a record-setting 78 days in 1853. A passenger list shows him as boarding the Northern Light in Punta Arenas, Chile, with the point of origin of his trip being the U.S.A. This suggests that he took a different ship from San Francisco to Chile, then transferred. He arrived in New York on January 14, 1856. By the time Samuel returned home in early 1856, he had been away for four years.

In the 19th Century, ships sailing around Cape Horn carried world trade from Australia to Europe, and also passenger and trade goods between the coasts of the United States. It was a recognized route for those going to the California gold fields. Though popular, the route was also extremely hazardous, and many ships foundered.

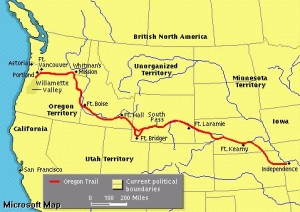

Wagon Train to Oregon

In 1859, Samuel and Marcellisse left their home in Monroe, Michigan for Oregon, which became a State that same year. Samuel organized and led a wagon train consisting of French-Canadians and other Monroe families, Samuel’s two younger brothers who had accompanied him on the first trip west, and “many sturdy young men, from Monroe and vicinity who were anxious to seek their fortunes in the promised land.” (The Monroe Democrat, 1912). The three Goulet children accompanied them: Phillip, age about 14, Fred, age about 10, and Mary Ellen, age 8. We don’t know what route the wagon train took, but probably they crossed through Michigan, Indiana, and Illinois on established routes, and joined the Oregon Trail in Iowa or Nebraska. They were on the trail for six months.

Giving Birth on the Trail

Marcellisse must have been as brave and adventurous as her husband. She was pregnant when the pioneer caravan left Monroe, and gave birth, as she must have known she would, on the trail, somewhere in Iowa. The new baby, named William Henry Goulet, was our direct ancestor and my mother’s grandfather. The circumstances of his birth must have been harrowing. According to the story told to my mother,

“The wagon train stopped only a few days for the birth. My great-grandmother lay in the wagon with her arms stretched out grasping the sides, to steady herself from the jolting wagon, so she wouldn’t inadvertently crush her baby lying beside her. The baby was very small at birth, and the Indians followed the wagon train for several days trying to trade for the baby, whom they thought was special because of his extremely small size.” (Alvis Whitelaw oral history, 1992).

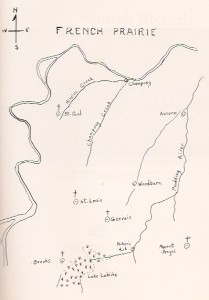

French Prairie

The pioneers settled on homesteads in an area near Salem, Oregon, just east of the Willamette River, called French Prairie. The area got its name from the French-Canadian trappers who had worked for the Hudson’s Bay Company in earlier years and had now retired to farms there. Samuel and Marcellisse had one more child, Minnie, born in 1862, and remained on their homestead near Gervais for the rest of their lives. They were considered to be ethical, upright people by their neighbors. Samuel’s Obituary says that he was

“a man of strict probity, of quiet disposition and a determined will, always busy at something and never satisfied until he had finished that which he had begun. He was a good neighbor, generous to a fault, and delighted in shouldering the burdens of others. He was a great mathematician, had a remarkable memory and had good presence of mind just prior to passing away. He built a number of houses in this section and was conscientious in the performance of duty.”

Mathias Goulet (1827-1903). He accompanied his brother Samuel on all of his travels and settled nearby in French Prairie, Oregon.

Samuel Goulet and his younger brothers, Mathias and Peter, uniquely among our ancestors, traveled throughout the entire Western Hemisphere. They journeyed by boat, horseback, and wagon train over vast distances from Quebec to the tip of South America, and from the West to the East coast of North America. In spite of these achievements, Samuel was a quiet, hard-working, thoughtful man; his brave and adventuresome explorations of the New World sat modestly on his shoulders.

William Henry Goulet (1859-1924)

William Henry, born on the wagon train, was the fourth of five children of Samuel and Marcellisse. He is my great-grandfather. Unlike his parents, he lived his entire life within a few miles of the family home, mainly in Woodburn. He was known for his élan and for his dedication to horses. He had a livery stable in town for many years, which was a hub for Woodburn transportation. He raced teams of horses at the county fair. He was the trusted town veterinarian, and was called “doctor”, though he had no formal medical training, and he was a Marion County Commissioner for many years.

His mother never learned to speak English, so French was the main language of his parents’ home, and he spoke it well. He converted to Protestantism at the time of his marriage to Florence Beach, a woman of British background. In this he had the acceptance of his parents, who were always kind and welcoming to his bride. He and Florence spoke only English in their own home, and he did not teach his children French. However, he did not change the spelling or pronunciation of his name, although his older brother attempted to Anglicize his name to Gouley.

Mary Ellen Manning (1851-1937), daughter of Samuel and Marcellisse Goulet, and a favorite great-aunt of my mother, Alvis Love Whitelaw.

William apparently identified with his French-Canadian background but did not feel that he had to maintain the language or culture. General assimilation was common in 19th century small town America, and the Goulets, like other French Canadians who settled in the Woodburn area, seem to have left behind much of their cultural heritage within a generation or two. Today educational displays at Champoeg State Park in the Willamette Valley preserve some of the cultural heritage of the French-Canadians who were among the first homesteaders there. (For more on William’s wife, Florence Beach Goulet, click here. For more on his daughter, Mabel Goulet Love, click here.)

How You Are Related to the Goulets, Duvals and Nadeaus

Go to your personal fan chart, and go back from Alvis Whitelaw.

References

Susan, Nancy and John Whitelaw at the gravestone of Michael Duval, the father of Marcellisse Duval Goulet. St. Antoine Old Burying Ground, Monroe, MI. 2011.

Bartolo, Ghislaine Pieters, and Reaume, Lynn Waybright (1988). The Cross Leads Generations On: A Bicentennial Retrospect of St. Mary of the Immaculate Conception formerly known as St. Antoine at the Raisin River. “Remaining Tombstones in Old St. Antoine/St. Mary Burial Ground on North Monroe Street” (Tappan, NY: Custombook Publ.). p. 96-98.

California Census, 1852. Calaveras County.

Death of Samuel A. Goulet (Jan. 11, 1906). Woodburn, OR: The Woodburn Independent, p. 1.

Denissen, Christien (1912, revised 1987) Genealogy of the French Families of the Detroit River Region 1701-1936. (Detroit, MI: Detroit Society for Genealogical Research). Vol. I.

Dr. W.H. Goulet called by death (Oct. 1924) Woodburn, OR: The Woodburn Independent, p. 1.

DuLong, John P. (2001) French Canadians in Michigan. (East Lansing, MI: Michigan State University Press.)

Hines, George H. (1919) Death List of Oregon Pioneers, “Gouly, P.P.” (Oregon Historical Quarterly, Vol. 20, April-May).

The Late Samuel A. Goulet. (1906) The Oregonian, Jan. 11. p. 6.

Marriages Paroisse L’Assomption de Windsor, Ontario 1700-1985. Societe Franco-Ontariene d’Hubire et de Genealogie. Ottawa, Canada. No date.

Michigan Pioneer and Historical Collections. (Lansing, MI) Vol. 10, p. 536-537 and p. 601-613.

Mortuary, Mrs. Antoine Goulet (Jan. 12, 1912). The Monroe Democrat, Monroe, MI, p. 12.

Munnick, Harriet Duncan (1981). Catholic Church Records of the Pacific Northwest. (Portland, OR: Binford and Mort, publisher.)

New York Passenger Lists, 1820-1957 [database on-line]. Ancestry. com, Provo, UT. 2010

Oregon Historical Society, Portland, OR,Index Collection: Territorial and Provisional Government Papers Index. retrieved from Ancestry.com Goulet, Samuel A., tax assessmet roll, Marion County, 1854, 1855.

Oregon State Archives and Records Center. Oregon Death Index 1903-1998. database: Ancestry.com

Portrait and Biographical Record of the Willamette Valley (1903). “Phillip Peter Gouley” (Chicago,Ill: The Chapman Publishing Co.) p.985.

Pioneer Woman Passes Away at Gervais (Dec. 26, 1911). The Oregonian, p. 6.

Rejected Applications, Oregon City Land Office. Genealogical Material in Oregon Donation Land Claims, abstracted from Rejected Applications Vol. 4, 1967, (Portland: Genealogical Forum of Portland) p. 25.

Russell, Donna Valley (1982). Michigan Census 1710-1830. (Detroit, MI: Detroit Society for Genealogical Research), p. 51 (Michigan Census, 1782), p. 66 (1796 census of Wayne County, MI) p. 76 ( 1802 Tax List), p. 80 (1802 Tax List for Wayne County) and p. 175 (1830 Michigan Census).

U.S. Census, 1840. Frenchtown Township, Monroe County, MI. Martin Nadeau; Michael Duvall.

U.S. Census, 1850. Monroe Township, Monroe County. Michael Duvall; Antoine Goulard.

U.S. Census. 1860. Fairfield, Marion, OR. S.A. Goulet.

U.S. Census. 1870. Marion County, OR. S.A. Goulet.

U.S. Census. 1880. Woodburn, Marion, Oregon. Samuel Goulett.

U.S. Land Office (1936) Monroe Harbor, Mich. Map Prior to 1820. (U.S. Army Corps of Engineers). Map rev. by Michael M. Dushane, April, 2012 and retitled “The First Land Claim Owners Along the River Raisin.” Dushane states that “Most owners possessed the claim prior to July, 1796.” The original map is at the Monroe Historical Society, Monroe, MI.

Williams, E.Gray and Ethel W.(1963). First Landowners of Monroe County, MI. (Kalamazoo).