“THAT SINGULAR GOOD OLD MAN”

According to family historian William DeLoss Love, “The name of Theophilus Whaley is familiar to every reader of early New England history. He is one of its most mysterious characters.” (p. 129) His biography is deeply connected to the events of the English Civil War, particularly the trial and execution of Charles I in 1649 by William Cromwell and his Puritan constituency in Parliament.

The Whaley family (also spelled Whalley or Whale) was on the side of Parliament, and were cousins of Oliver Cromwell, the leader of the Parliamentary rebels. One prominent member of this family was Edward Whaley. He was among the fifty-nine judges who condemned Charles I to death. After his execution, Cromwell and the Puritans ruled England until 1660, when Charles, son of the executed king, was invited back from exile to become King Charles II. From then on, the judges who signed his father’s death warrant were in danger, and many fled the country. Some, including Edward Whaley, came to the American colonies, where citizens hid them from the arm of English law. In the colonies there was an atmosphere of mystery and confusion surrounding these fugitive and hidden judges who were supposedly living among them. People speculated on whether a newcomer or stranger was possibly one of the fugitives.

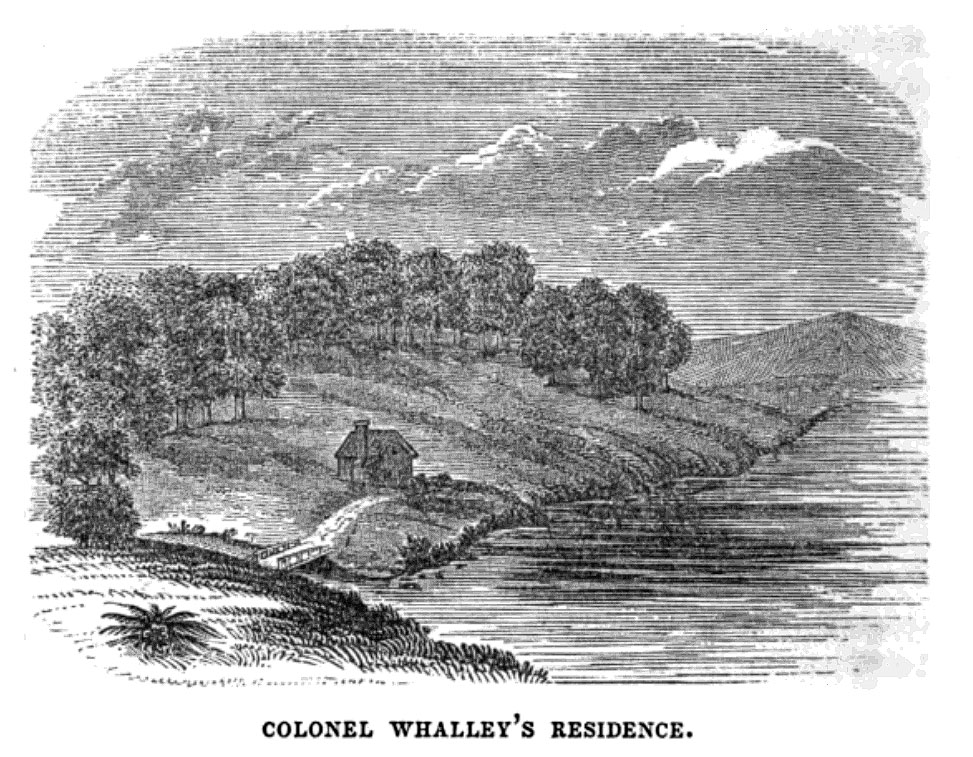

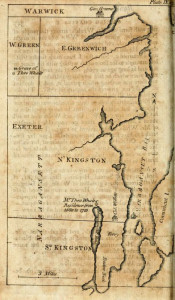

Theophilus Whaley entered this scene in 1679, when he came to Rhode Island from Virginia with his wife and children. The family settled in a modest cabin on Pettaquamscutt Pond in what is now North Kingstown. Several things about him seemed mysterious, most prominently that he never gave a full account of his background, and that he had arrived in Rhode Island in the same year that Edward Whaley supposedly died while in hiding, and that he shared the same name as Edward Whaley. In the community there was speculation bordering on conviction that he was in fact Edward Whaley. The mystery of Theophilus’s true identity was still unsolved at the time of his death in about 1720. (Pictured: the Judges Cave near New Haven, CT where Edward Whaley lived in hiding at various times.)

The Judges Cave near New Haven, CT where Edward Whaley lived in hiding at various times. Painting by George Henry Durrie

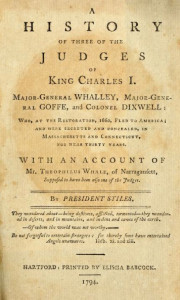

In 1755, thirty five years after Theophilus’s death, Dr. Ezra Stiles, President of Yale University, began a study of judges who had been sequestered in New England. He was able to interview children and close neighbors of the judges, and to examine documents. He published a book on his extensive study in 1794, and, as the cover indicates (pictured at left), the book contained “An Account of Mr. Theophilus Whale, of Narragansett, Supposed to have been also one of the Judges.”

Dr. Stiles learned that Theophilus Whaley was born in England in about 1616-22, and that he was of good descent and education. Whaley said that when he was young “he was brought up delicately and that till he was eighteen years old, he knew not what it was to want a servant to attend him with a silver ewer and knapkin whenever he wanted to wash his hands.” (Stiles, p. 351) When he was about 18 years old, in 1637, he came over to Virginia, and went as an officer into the Indian wars. Then he returned to England and became “an officer in the parliament wars, and through the Protectorate, “ or the reign of William Cromwell (Stiles, p. 355).

After the Restoration of the monarchy in 1660, Whaley returned to Virginia, “having by some action or other rendered himself obnoxious to the royalists.” (Stiles, p. 355) He never said how he was involved in the events of the English Civil War, but he considered himself “a man of blood” who might be in danger from the royalists. Once back in Virginia, he married in about 1670, when he was about fifty years old. His wife, Elizabeth Mills, was a Virginian. They lived there for about ten years. Virginia records show that he was a man of some wealth and property. We don’t know why the family left Virginia; possibly he began to fear that he was being pursued by English authorities there. Or they may have run into some religious difficulty; the Church of England was dominant in Virginia, and Whaley was a Baptist.

In 1679-80 the family moved to Rhode Island, and rented property on Pettaquamscutt Pond, where they built a modest cabin. There Theophilus lived a simple and retired life, supporting himself and his family largely by fishing and weaving. His neighbors soon learned that he was a man of learning, proficient in Greek, Latin, and Hebrew, and called upon him for writing documents and other such work. He was given much to study and reflection.

Dr. Stiles reported incidents that deepened the neighbors’ suspicions that Theo. Whaley was perhaps one of the judges. A delegation of distinguished Bostonians visited him about once a year. The visitors “embraced him with great ardor and affection, and expressed great joy at seeing him, and treated him with great friendship and respect.” These men also supplied him with means, possibly money coming from relatives in England. The neighbors who observed these visits concluded that the Bostonians knew his true identity and had known him in Boston as Edward Whaley. Another time, a British warship under the command of an officer named Whaley anchored at Naragansett Bay. The captain came ashore and visited Theophilus. The neighbors saw them greet each other warmly; it was clear that they had known each other before. The captain invited Theophilus back to his ship, but Theophilus declined. The neighbors concluded that he feared he might be betrayed by someone on the ship and deported to England for trial.

Although Theophilus’s children and neighbors were all certain that he was Edward Whaley, in the end Stiles was unconvinced. He had fairly strong documentary evidence that Edward Whaley had in fact died in 1679 while in hiding, and that therefore Theophilus could not be the same man. He also pointed out that it did not make sense that Theophilus would have chosen to retain his last name and only change his first name, if he were truly trying to hide from the English authorities.

However, the mystery of his true identity still remained, and it was clear that he was hiding from something in his past. The most likely possibility that Stiles considered was that Theophilus was actually Robert Whaley, a younger brother of Edward Whaley. Robert had served during the Civil War in the regiment of Commander Hacker, who was the commanding officer at the execution of King Charles I. Presumably, Robert participated in this event as a member of the regiment. At the time of the restoration of the monarchy in 1660, Hacker was executed in retribution for his role in the regicide, so it was reasonable that others in the regiment would be fearful of arrest. Robert’s name disappears from English records at about the time of the restoration, and this is also the time when Theophilus appears in Virginia. So it has seemed quite possible to Stiles and to subsequent historians that Theophilus may have been Robert (Whaley, 1901). If he was involved in Charles I’s execution, he may have come to regret it later. His reference to himself as a “man of blood” who “ought to mortify himself” may suggest his participation and subsequent change of heart. Other participants in the regicide are known to have lived with this haunting sense of guilt that shadowed the rest of their lives.

Whatever Theophilus’s true identity, he was considered a good and pious person by his neighbors and children. Stiles (p. 352) referred to him as that “singular, good old man.” He and his wife Elizabeth raised five children to adulthood, including Samuel, our direct ancestor. Theophilus spent the last years of his life “in solitude and without labor; yet his body and mind were sound to the last.” After the death of his wife, about 1715, he went to live with his daughter Martha in West Greenwich. He died between 1719 and 1722, probably in the latter year, at the remarkable age of 103 years. He was buried near the home on Hopkins Hill, it is said with military honors.

The graveyard on Hopkins Hill still exists. When William DeLoss Love visited it in the early 20th century, he reported that Whaley’s grave was “known but unmarked.” In 1992, a local historian, Howard Goldman (p. 32), reported that the cemetery was small and overgrown, surrounded by the remains of a stone wall, and contained ancient, rough cut stones on which the inscriptions had worn off. Goldman also noted the appearance of a commemorative stone to Whaley, of modern origin. This stone must have been placed somewhere between the early 20th century, when W. D. Love visited, and the early 1990s. There are no records showing who was responsible for placing the memorial there.

The memorial stone reads:

“Here was buried

Theophilus Whale

The singular good old man

Born in England about 1616

Died on this hill about 1720.And his wife

Elizabeth Mills

Of VirginiaTheir descendents endure

Even unto this day”

And so, fittingly, the Theophilus Whaley story ends with another mystery. Who placed this stone and why did they do it? It seems to be a testimony to our continuing fascination with this “singular, good old man.”

ELIZABETH (MILLS) WHALEY (1645-1715)

Map showing the Whaley home site and grave site near Narragansett Bay, Rhode Island. (Stiles, p. 344a.)

Theophilus’s wife, Elizabeth, was born about 1645, probably in Virginia. We know nothing about her early life. In later years she signed legal documents with her mark, often a sign that the person could not write, so she may not have received much education as a girl. She married Theophilus in about 1670, in Virginia, when she was in her mid 20s. He was much older, being nearly 50. So far as we know, this was a first marriage for both of them. They had two daughters, and possibly two more children, while in Virginia, but in 1679-80 they moved to Rhode Island, where they raised a total of five children to adulthood. They lived very modestly. According to Dr. Stiles, Theophilus lived in “poverty and obscurity, and built himself a little under-ground hut in a high bank, or side hill, at the north end or head of the pond.” (p. 342).

Dr. Stiles, in interviews with descendants and acquaintances of the Whaleys, learned something of Elizabeth’s character. Judge Hopkins, a grandson, remembered his grandmother as a “smart tight little woman, a mighty doctress” [a woman with medical skills] (Stiles, p. 346.) Judge Hopkins also remembered that when the couple became old, Elizabeth used to “make long visits to her daughters. . . and leave the old man to shift for himself” (p. 348). One reason she might have done this comes from an anecdote from a neighbor who knew them well.

“The wife was a notable woman, a woman of high spirits, and often chastised her husband for his inattention to domestic concerns, and spending so much of his time in religion and contemplation, neglecting to repair and cover his house, which was worn out and become leaky and let in rain in heavy storms, which used to set her a storming at him. He used to endeavor to sooth her with placid mildness, and to calm her by observing in a storm, while the rain was beating in upon them, that then was not a time to repair it, and that they should learn to be contented, as it was better than sinners deserved, with other religious reflexions; and when the storm was over, and she urged him, he would calmly and humorously reply, it is now fair weather, and when it did not rain they did not want a better house.” (Stiles, p. 351)

Perhaps she stayed in the homes of her daughters because she wanted to be in a dry house. Elizabeth died in about 1715 and was buried near the church in Kingston, RI.

The Whaleys’ youngest child and only son was Samuel Whaley. Samuel’s granddaughter, Sarah Blanchard, married Sgt. Robert Love, the son of Adam and Mary Love, who were the subject of my last family report. From Sarah and Robert Love descended a series of male children, culminating in Olin Love, my grandfather.

How you are related to Theophilus and Elizabeth Whaley

On your personal Ancestor Fan, go to the outermost ring and find Levi Love. Then click here to open the Levi Love Ancestor Fan. Theophilus and Elizabeth Whaley are in the green section, fifth ring out.

References

www.findagrave.com

Goldman, Howard A. “That Good Old Man – Whoever He Was.” Old Rhode Island, vol. 2, Issue 6. July, 1992. pp. 32-40.

Love, William De Loss. Love Family History. Unpublished Manuscript. New Haven, CT, 1918. P. 129.

Stiles, Ezra. A History of Three of the Judges of King Charles I. Major-General Whalley, Major-General Goffe, and Colonel Dixwell: Who at the Restoration of 1660, Fled to America; and were Secreted and Concealed, in Massachusetts and Connecticut, for Near Thirty Years. Hartford, CT: Printed by Elisha Babcock, 1794.

Updike, Wilkins. History of the Episcopal Church in Narragansett, RI. New York: H.M. Onderdonk, 1847. Picture of the Whaley home, p. 352.

Whaley, Rev. Samuel. English Record of the Whaley Family and Its Branches in America. Ithaca, N.Y: Andrus & Church, 1901).