The world into which our ancestors, William Bradford and Alice Carpenter, were born in 1590 was dynamic and unstable. It was a time of the Renaissance flowering of literary and artistic genius. William Shakespeare was currently at the peak of his writing career. Queen Elizabeth I had just led her small, upstart nation to victory over the invading Spanish Armada, an event that changed the power balance of Europe.

Galileo, a near contemporary of the Bradfords. He was an astronomer and a pioneer of the scientific revolution.

The Protestant Reformation and advances in astronomy, mathematics, and physics had thrown old religious certainties into confusion. A century of ocean exploration had opened Europeans’ minds to possibilities of leaving behind the problems of their home countries and starting new communities in previously unknown lands.

Joining the Separatists

William Bradford’s family were prosperous farmers in the northern English county of York, but his childhood years were marked by separation, loss, and instability. His parents both died when he was young, and he was passed around to various relatives. He was a sickly, bookish child; unable to help much with farm work, he spent his time reading, especially the Bible, and teaching himself Greek and Latin.

He became involved with a new and controversial religious sect in the nearby town of Scrooby. The members were called Separatists because they believed in the total separation of their own, small, community of like-minded believers, from the Church of England, which they saw as corrupted by power, and weighed down with meaningless ritual. Because of their refusal to adhere to the official state religion, they were considered to be a subversive element and were persecuted.

Persecution increased when King James I inherited the throne in 1603. Bradford recorded in his journal, Of Plymouth Plantation, that church members:

“were hunted and persecuted on every side, so as their former affliction were as flea-bitings in comparison with these that now came upon them. For some were taken and clapt up in prison, others had their houses beset and watcht night and day, and hardly escaped their hands; and the most were faine to flie and leave their howses and habitations, and the means of their livelihood.”

In 1608, when William Bradford was 18, he and other members of the Scrooby congregation decided to escape persecution by immigrating to Holland, which was tolerant of religious diversity. The congregation lived in Holland for twelve years. During that time William turned twenty-one and inherited all the English property of his parents, which he immediately sold. In Holland he met his future wife, Alice Carpenter, whose family were also English Separatists. Alice and William did not marry at that time; each married instead another member of the congregation. William at age twenty three married Dorothy May, then sixteen, and Alice married Edward Southworth.

Life in Holland had drawbacks. As non-citizens, the English Separatists were barred from the more lucrative areas of Dutch economic life. William supported Dorothy and son John with a low-paying job in the textile industry. Children were assimilating into Dutch culture and attenuating their allegiance to Separatist values. Catholic Spain was threatening an invasion of the Netherlands. In the midst of these hardships, reports were coming in of vast unclaimed lands across the Atlantic Ocean in North America. For the bold and adventurous, this new land offered tantalizing possibilities for religious and economic freedom.

By 1620, the Scrooby congregation was planning to immigrate to North America. Bradford explained in his journal:

“all great & honourable actions are accompanied with great difficulties, and must be both enterprised and overcome with answerable courages. It was granted ye dangers were great, but not desperate; the difficulties were many, but not invincible. For though their were many of them likely, yet they were not cartaine; it might be sundrie of ye things feared might never befale; others by providente care & ye use of good means, might in a great measure be prevented; and all of them, through ye help of God, by fortitude and patience, might either be borne, or overcome. “

The Mayflower Voyage

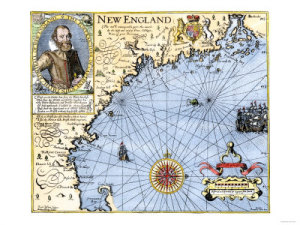

1609 Map of New England, by John Smith, the founder of Jamestown colony in Virginia. The pilgrims almost certainly had this map on the Mayflower.

William Bradford was 30 years old when he crossed the ocean on the Mayflower, and his wife, Dorothy, was about 23. They left their young son John in the care of friends in Holland, planning that he would come over with a later contingent of immigrants.

Along with a crew of about thirty men and boys, the Mayflower had one hundred and two passengers. Only eighteen were adult women; all of these were married and three were pregnant. We are used to hearing about the “Pilgrim Fathers” so it may be a surprise to learn that that the passengers were quite young. The adults were mainly in their twenties and thirties. Over forty of the passengers were children, a large proportion of whom were teenagers, both boys and girls. Most of the passengers were in family groups, but a significant number, especially among the adolescents of both sexes, were servants connected to a family through legal indentures.

The Mayflower during one of the many squalls it endured. The crew had to lower the sails to keep the wind from breaking the masts, so the ship was simply tossed around on the sea, soaking the terrified passengers.

Only about thirty of the passengers were from the Separatist congregation in Holland. The rest were residents of England; most of these were also Separatists or at least sympathetic to their religious convictions. A few may have been strictly economic immigrants. Also on board were many animals: farm animals such as chickens, pigs, and sheep, and cats to keep down the rodent population. Two dogs came along as pets, a mastiff and a springer spaniel.

The two-month trip across the ocean was a terrible ordeal; only one person died, a member of the crew, but all were sick and dirty the whole way over. They were cramped and crowded, often wet and in great danger from ocean storms, and didn’t have enough decent food.

Beginning of Democracy in America

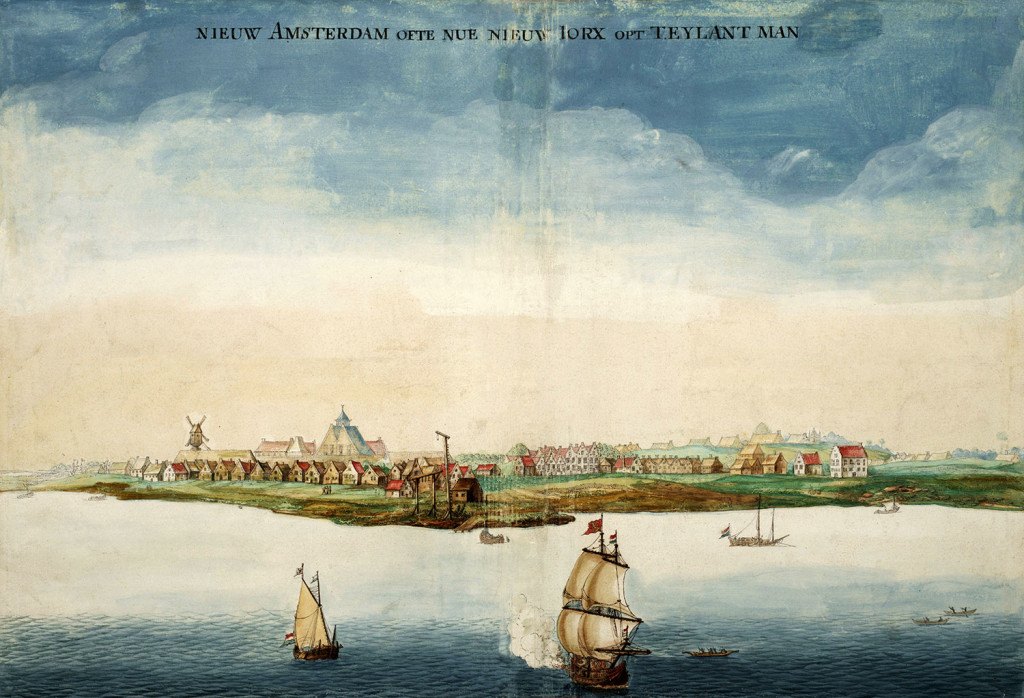

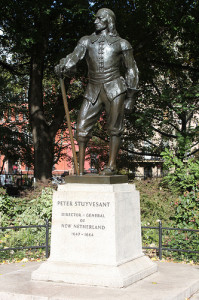

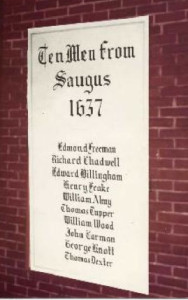

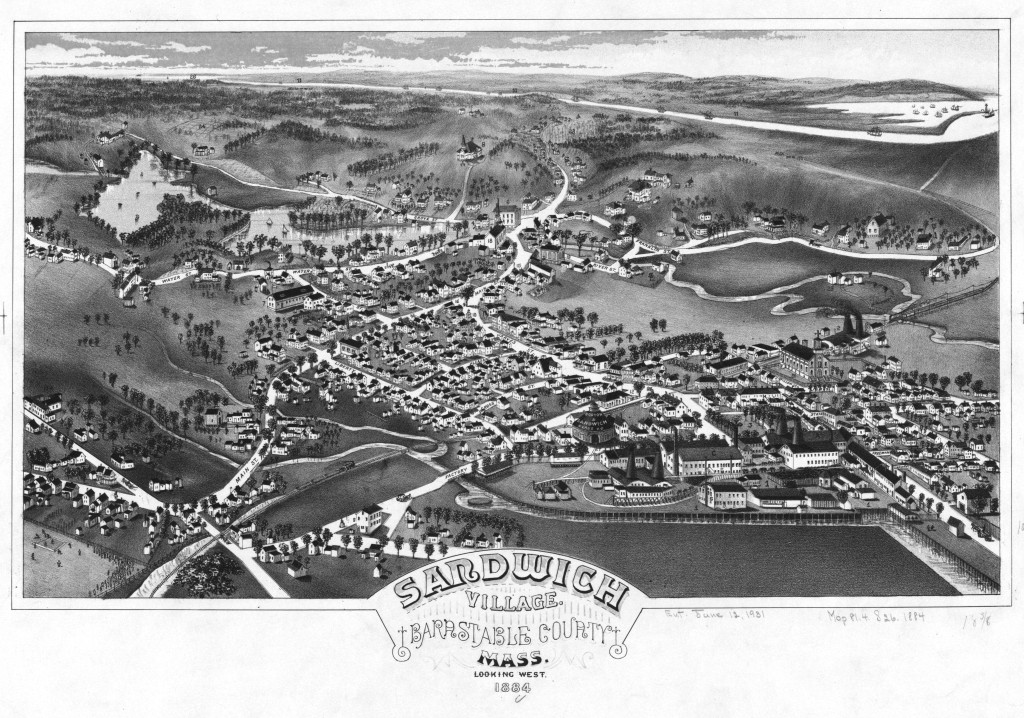

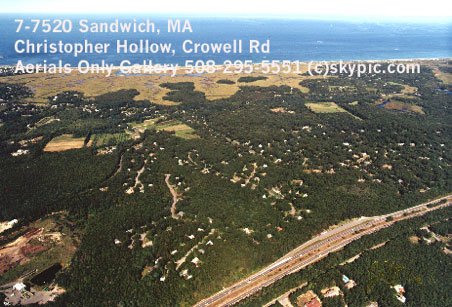

King James had given the Mayflower passengers permission to form a settlement in what is now New York, but the ship ended up, probably due to bad weather, north of there, on Cape Cod, Massachusetts. The King had not yet claimed the right to rule this area, so the legal auspices under which the new settlement was to manage itself were unclear.

Some passengers suggested that they did not need to submit to any government and each person could go off on their own. However, it was obvious to most that if they were to survive the winter, they needed to work together, and so the adult men on the ship formed and signed the Mayflower Compact.

Each signer voluntarily agreed to submit to a democratically elected governing structure, consisting of a governor and a group of “assistants.” This document has been celebrated as the beginning of democracy on American shores. William Bradford was one of the architects of the document and among the first signers.

When the Mayflower arrived off the shore of Cape Cod, William Bradford was among the small group of men who first set foot on shore. It was now November, and they had to work quickly to find a suitable place for a settlement. They urgently wanted to make contact with the local inhabitants to trade for food and seed grain, and to establish friendly relations. Indians appeared from afar, but disappeared into the woods when the pilgrims tried to approach. The pilgrims came upon an Indian settlement that had been deserted, due to an outbreak of small pox brought by earlier European explorers. They also found baskets of Indian corn buried in the sand, which they dug up and took with them. They desperately needed provisions, and hoped to offer trade goods to the Indians in compensation. Possibly in retaliation for this theft, a group of Indians attacked the exploring party one night, but were successfully fended off. Later on, after the Indians and pilgrims became acquainted, the pilgrims paid the Indians for the corn they had taken.

The first winter was horrendous. Half of the pilgrims died, mainly from infectious diseases. The women were particularly hard hit: all but four of the eighteen women died. The women remained on the Mayflower all winter, in close, damp, dirty quarters. The men were mainly on land, hunting, fishing, and building rough shelters for the families to inhabit in the spring. They endured great hardship, but were in healthier surroundings than the women, and had access to fresh water. If they were sick, they returned to the Mayflower, inadvertently further infecting those quarters. Dorothy Bradford was among the first casualties; she died not from sickness but by falling overboard while her husband was on one of the early scouting parties. William himself got very ill during that terrible winter and almost died.

The First Thanksgiving

By spring of that first year, it began to seem possible that the colony might survive. There were no more deaths. The pilgrims learned from the Indians how to plant such native foods as corn and squash, and how to fish the local waters. The Mayflower sailed back to England, and families established themselves in the newly-built houses.

After the first elected governor of the colony died during the winter, William Bradford was elected as the new governor, a position to which he was re-elected nearly every year until his death in 1657.

Artist’s rendering of the first Thanksgiving, 1621. William Bradford, seated at the table, is presiding over the feast in his role as governor.

During the autumn, the settlers were able to harvest enough food to last through the winter. In celebration, they organized a feast that went on for several days. Ninety of their Indian neighbors brought newly killed deer and joined the party. The four adult women who had survived the winter must have been strained to the utmost to organize the cooking for this large crowd of about 140 people.

Alice Carpenter Southworth

In 1623, when she was thirty-three years old, Alice Carpenter Southworth, along with other Separatists from Holland and England, came to Plymouth on the ship Anne. Her husband, Robert Southworth, had recently died, leaving her with two young sons. Probably by prearrangement, within a month of landing in Plymouth she married her old friend, the widowed William Bradford. In the following years, three of her sisters also came to Plymouth; they formed an influential nucleus of the community of women in the colony, and among them left many Carpenter descendants. Plymouth records note that Alice was much loved in the colony.

The wedding of the colony’s governor and Alice, both of whom were well known, was the occasion for a major celebration. The Native American leader, Massasoit, attended with his wife and a retinue of over 100 men. The party feasted on venison and the increasingly bountiful supplies of the pilgrim colony.

Over the years the Bradfords raised a number of children. William’s son, John, and Alice’s two sons, Thomas and Constant, came to the Bradford home from Europe. The Bradfords had three children of their own. Our family descends from William and Alice through their first son, William Jr. They also fostered other children of the colony.

Governor Bradford

William Bradford was governor of the Plymouth Colony, with only a few breaks, from its beginning until his death in 1657. One of his main tasks was to put the colony on a sound financial footing. The original voyage was financed by a group of investors in England. They needed to be paid off through the profit making ventures of the colonists, which consisted mainly of sending beaver furs, lumber, and smoked fish back to English markets. Vagaries of weather, shipwrecks, and other perils interfered with this transatlantic trade, but the colony was able, after several years, to free itself of debt. Thereafter, Bradford led the colony in a transition from a communal economy, where everything was owned in common, to one of individual ownership.

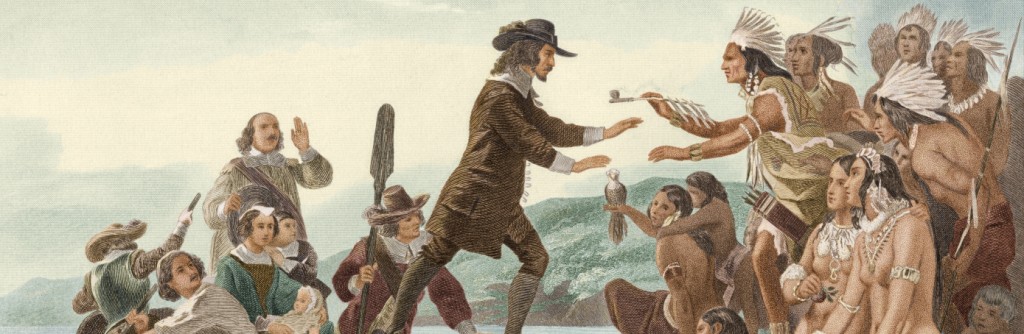

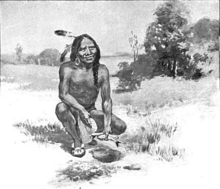

Squanto, an early benefactor of the pilgrims, teaching them how to plant corn using fish as fertilizer. Squanto had learned English from earlier explorers and had travelled to Europe. He was a key intermediary for the pilgrims in establishing good relations with the local inhabitants of Cape Cod.

Another major task was to maintain good relationships with their Native American neighbors. The pilgrims traded with the Indians for beaver pelts, a major source of income for the colony. When the pilgrims set up outposts in Connecticut and Maine for trapping and logging, they needed the good will and the expertise of the Indians. It seems very unlikely that the Plymouth colony could have survived without the active help and support of the surrounding Native Americans.

Beyond the practical considerations, the religious values of the Separatists led them to policies of toleration and mutual respect. They practiced these values with the Native Americans, and also with religious dissenters such as the Quakers. They accepted the presence of economic immigrants to their colony, some of whom were rough, noisy, and caused trouble with the Indians. As part of this policy of respect for diversity, the Plymouth colony established the principle separation of church and state. In this way, they could accommodate non-Separatists in their midst, as long as they obeyed the civil governmental structure of the colony.

In their practice of gentle toleration, the pilgrims of Plymouth colony were very different from the mighty Massachusetts Bay colony growing on their border. The English Puritans who settled there were high-handed in their dealings with others, and intolerant of religious dissent. The painful history of European settlers’ treatment of the Indians began early, and it is extremely unfortunate that the model for working with local populations established by the Plymouth colony was not followed.

Another of Bradford’s responsibilities as Governor was to maintain order and stability within the diverse Plymouth community. The following excerpt from his journal, On Plymouth Plantation, shows the respectful but firm leadership he exercised. The Separatists did not celebrate Christmas as a religious holiday, but some newcomers to the colony, who were there only for economic gain, wanted to celebrate the holiday in traditional English fashion. Bradford wrote in his journal:

“And herewith I shall end this year. Only I shall remember one passage more, rather of mirth then of waight. On ye day called Christmas day, ye Govr [William Bradford] caled them out to worke, (as was used,) but ye most of this new company excused them selves and said it wente against their consciences to work on yt day. So ye Govr tould them that if they made it mater of conscience, he would spare them till they were better informed. So he led away ye rest and left them; but when they came home at noone from their worke, he found them in ye streete at play, openly; some pitching ye barr, & some at stoole ball, and shuch like sports. So he went to them, and tooke away their implements, and tould them that was against his conscience, that they should play & others worke. If they made ye keeping of it mater of devotion, let them kepe their houses, but ther should be no gameing or revelling in ye streets. Since which time nothing hath been atempted that way, at least openly.”

William Bradford died in 1657. He left his children and his widow, Alice, a sizable estate, including a library of over 100 books. Alice survived until 1670, when she was eighty years old. Their son William became a leader of the colony and in the military.

The Mayflower Society, an organization of the descendants of the Mayflower, estimates that there are about ten million descendants living today of the original passengers on the Mayflower; some unknown number of these descend from William and Alice Bradford. (MacGunnigle, 2015).

In a larger sense, all of us in America today are the beneficiaries of Bradford’s legacy. Through the Mayflower Compact, he was a pioneer in establishing democratic government as a viable alternative to monarchy. He had the vision and leadership to promote the immigration of a small community of religious dissenters to a new and unknown land across a dangerous ocean. His good judgement and dedication guided the colony in its early years of near extinction and made it a model of good governance that still informs our national aspiration to become a true beacon of democracy.

Bradford himself articulated what he hoped would be the legacy of the pilgrims of Plymouth colony. It is helpful to remember that his understanding of the “kingdom of Christ” meant living out the values of toleration, community, respect, mercy, caring, humility, and the obligation of each person for self-governance.

“Lastly (and which was not least) a great hope, & inward zeal they had of laying some good foundation (or at least to make some way thereunto) for ye propagating & advancing ye gospel of ye kingdom of Christ in those remote parts of ye world, yea, though they should be but even as stepping stones unto others for ye performing of so great a work.”

How You Are Related to William and Alice Bradford

On your individual fan chart, find Eunice Waldo in the outermost arc. Then click here to trace Eunice Waldo’s ancestry back to the Bradfords. This line of descent from William and Alice Bradford to our family has been approved by the Mayflower Society and the documentation of it is stored in their permanent records.

References

Anderson, Robert Charles. The Pilgrim Migration: Immigrants to Plymouth Colony, 1620-1633. Boston: New England Historic Genealogical Society. 2004.

Bradford, William. Of Plymouth Plantation (1620-1647). New York: The Modern Library. 1981.

Heath, David B. (Editor) Mourt’s Relation: A Journal of the Pilgrims at Plymouth. Bedford, MA: Applewood Books. 1963.

Johnson, Caleb H. The Mayflower and Her Passengers. USA: Xlibris Corporation. 2006.

http://mayflowerhistory.com/women

MacGunnigle, Bruce C. From Fifty to Ten Million: A Sample of the Families on the Mayflower. The Mayflower Quarterly. March, 2015. Vol.81, No. 1. pp. 36-44.

http://www.pilgrimhallmuseum.org/william_bradford.htm

Stratton, Eugene Aubrey. Plymouth Colony: Its History & People, 1620-1691. Provo, Utah: Ancestry Publishing. 1986.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Squanto

Williams, Mrs. Harold Four-Footed Pilgrims. The Mayflower Quarterly. Feb. 1975, Vol. 41, No. 1.

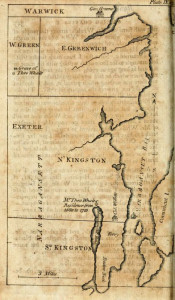

Their destination, Rhode Island colony, had been founded by Roger Williams a century earlier, and was known for its religious toleration and acceptance of a diverse array of immigrants. We don’t know if the Loves chose Rhode Island, or whether they wound up there because the neighboring colonies, Massachusetts and Connecticut, did not want them. Those colonies welcomed only Puritans from England who wanted to live in a theocratic state – in other words, immigrants who were like the people who were already there. The Loves immigrated primarily for economic reasons, not because of religious persecution. But they were no doubt aware that freedom of conscience was the bedrock on which Rhode Island was founded.

Their destination, Rhode Island colony, had been founded by Roger Williams a century earlier, and was known for its religious toleration and acceptance of a diverse array of immigrants. We don’t know if the Loves chose Rhode Island, or whether they wound up there because the neighboring colonies, Massachusetts and Connecticut, did not want them. Those colonies welcomed only Puritans from England who wanted to live in a theocratic state – in other words, immigrants who were like the people who were already there. The Loves immigrated primarily for economic reasons, not because of religious persecution. But they were no doubt aware that freedom of conscience was the bedrock on which Rhode Island was founded.