Amos Beach was born on a farm near Grand Rapids, Michigan, the third oldest of a sibship of seven. His parents had homesteaded land newly acquired from the Indians, and growing up Amos would have had the chance to observe Indian families camped along the Thornapple River. He lived through the gradual establishment of the nearest town, Middleville, which started as a stage coach stop and gradually added a general store, a blacksmith, a grist mill, a shoemaker and a carpenter. (Rosentreter, 1979) Amos grew up to fight in the Civil War, and later migrated to Woodburn, a small agricultural community in Oregon. In his old age he was a renowned local citizen, sometimes featured in the local newspaper for his colorful exploits and his memories of the Civil War.

Civil War

COME YOU WOLVERINES. Custer leads the Michigan Brigade, Gettysburg, July 3, 1863. By Don Troiani.)

Amos Beach‘s life entered the stage of history at age 20 when he and his brother John joined the Union Army to fight in the Civil War (U.S. Civil War). Michigan was strongly pro-Union and about 90,000 Michigan men fought in the war. Amos and John enlisted as privates in the 6th Regiment of the Michigan Cavalry Brigade, on September 20, 1862. (Dunbar & May). The Michigan Cavalry Brigade, also known as the “Wolverines,” was led by the dashing General George Custer. The soldiers were mounted on horseback and fought with sabers as well as pistols and rifles. The Wolverines, as part of the Army of the Potomac, fought in all of the major battles in the Eastern front against Lee’s confederate army. In addition to Gettysburg, the Michigan Cavalry Brigade fought mainly in Maryland and Virginia. (Urwin.) Today a large monument at the Gettysburg battlefield commemorates the Brigade’s contribution to the war effort. The obituary reprinted below lists all the battles in which the Brigade participated.

In his later year years, Amos Beach became a town character and told colorful stories about his war experiences. It is not always possible to reconcile these stories with the facts of the Civil War; however they do illustrate that Amos Beach continued to identify himself strongly as a Civil War veteran for the rest of his life.

An example of Beach’s war memories is in the historical museum at Woodburn, Oregon. Attached to a cord tied to a confederate uniform hat is a large tag. “Written in his own hand,” Beach wrote this story on the tag:

Michigan Cavalry Brigade Monument, Gettysburg Battlefield

“Captured by Amos Beach in 1863 at Rackoon Ford on the Rapidan River from Brigadier General Stewart Commanding the Louisiana Tigers after my escape from Rebbel Prison in which I staid 5 days being fed during the entire time ½ pt. of flour. Said hat cord was cut by a ball shot at him by one before being captured by his command, on being taken to him when captured, I was cursed and my life threatened. Then I was sent to prison to starve. Then a few days after I got back to my command he was captured while under guard. I snatched his hat from his head and kept it and this cord leaving him bear headed to continue his onward march to Prison hoping that he is enjoying the comfort enjoyed in that lake not made by a man nor in the heavens.” (transcribed by Shelley Downs, 1986, Woodburn, OR)

It is very possible that Beach was taken prisoner during the skirmishes around the Rapidan; we know that a number of Union cavalry were captured in these encounters. Beach also recounted that he escaped from prison and was hidden from the Confederate Army by “friendly negroes.” The rest of the story cannot be reconciled with the facts of J.E.B. Stewart’s life, but does show Beach’s vivid and personal style of recounting his war experiences.

After Lee’s surrender in 1865, the Brigade participated in the Grand Review for President Lincoln in Washington, DC on May 23, 1865. However, instead of being demobilized, the Michigan Cavalry Brigade was sent west to combat Indians. According to Beach’s obituary:

“[T]hey were taken down the Ohio river, across plains and mountains to Fort Leavenworth, Fort Laramie and further on, to stop the depredations of the Indians. They were greatly disappointed, not knowing that they were to be used to fight “Injuns”, not finding out the purpose of the movement until they reached St. Louis. It took 38 days to go from Leavenworth to Laramie and they had several fights with the Indian tribes, Sergt. Beach seeing many men, women, and children scalped and killed.” (Death Calls Amos Beach).

He was in the West for six months, but was finally discharged from the army on Nov. 24, 1865 from Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, with the rank of Sergeant, at the age of 23. During the Civil War the Michigan Cavalry Brigade had a total enrollment of 6,120 men, of whom 265 were killed in action, 120 died of wounds, and 880 died of disease, for a total casualty rate of 21 percent. This casualty rate was about average for the Union Army as a whole. (Harvey)

Marriage and Family

In tracking down the graves of Amos’s parents, I learned that his father died in 1863 and his mother a year later while he was away fighting. It seems safe to say that these losses would have added to whatever trauma and dislocation Beach might have been feeling as a result of his war experiences.

Four months after he returned to Michigan, in March, 1866, Amos married a local young woman, Clara Hatton. Amos and Clara had two children who died in infancy, and six more whom they raised on their farm in Thornapple Township, Michigan, near Grand Rapids. In 1883 Clara died from an accident with a horse and buggy, leaving Amos a widower at age 41 with a large, young family (Whitelaw, Alvis).

Marshall of Woodburn, Oregon

According to his great-grand daughter, Alvis Whitelaw, Amos had discussed moving to Oregon for many years, but his wife, Clara, was opposed. Her death, though sincerely mourned, removed a barrier to the plan. Amos and his brothers, John and Lauriatt, all moved to Oregon with their families in the 1880s by transcontinental train. Amos and his six children arrived in Woodburn in 1886. At that time, Woodburn was a newly founded small town on the Willamette River, near the state capitol, Salem. It was the center of an agricultural community. When Amos arrived in Woodburn, his six children, five girls and a boy, ranged in age from 16 to about 2 years old.

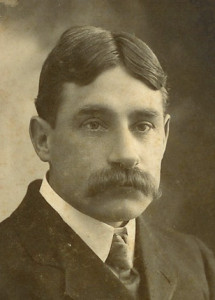

Amos Beach in later years.

Beach became the first Marshall of Woodburn. Located at a railroad junction, the town had a problem with tramps, men who traveled by hiding in box cars, and it was Beach‘s job to move the vagrants out of town. For this he received about $50 a year in salary. He had a reputation for eccentricity, feistiness, and personal courage; his career as Marshall was legendary. Gene Stoller compiled these stories for an article in the Woodburn Independent in 1987, about 60 years after Beach’s death, quoting articles that had appeared much earlier.

“Thirty-one hobos run out of town was Marshal Beach’s record Saturday. The marshal goes about it in a very nice manner. He approaches a gang and accosts them with, ‘Traveling?’ With lighted countenances, glad that someone is taking an interest in them, they reply, ‘Yes. .’ ‘Then,’ says the Marshall, ‘git!’ and they git, for the sudden gleam that comes into the officer’s eye satisfies them that he means business. They think at first that they have met with a Good Samaritan, but soon learn their error. Many are tough looking cases.”

Stoller also reported that:

Those who remember him say that he was not afraid of anyone. His fearlessness almost proved his undoing at one time when he attempted to bring in, single handed, several suspected criminals whom he had apprehended near the Pudding River bridge on the road to Mt. Angel. The men rushed Beach, took his gun, dumped him unceremoniously into a mud puddle and made their escape. Beach was outraged at this treatment and considered it one of the most humiliating experiences of his life.”

Mary, Sarah, George, Amos, Jeannette, Florence, and Laura Beach, Woodburn, Oregon

According to Stoller, the townspeople remembered Beach’s vigorous way of celebrating the Fourth of July.

“He had a small brass cannon which he loaded with black powder and fired to salute the dawn of Independence Day. He also added emphasis to many a local celebration by slowly walking down the railroad track to the north of town, dropping home-made bombs with short fuses. He had fuses of proper length and timed his walking speed so that he was safely out of the way when the bomb exploded. Old timers can remember the series of blasts set off in this manner.”

Beach continued to relive his Civil War experiences for the rest of his life. Stoller reported that:

“Beach’s grandson, Glenn Goulet, prevailed upon his grandfather to go to the showing of the motion picture, “Birth of a Nation,” in 1916. The old marshal, then in his 70s, at first didn’t want to go as he felt that movie actors couldn’t do justice to the portrayal of the great civil war in which he had fought. Goulet finally convinced the elderly man and they attended the show together.

“[T]hey watched, spellbound, Beach became completely captivated by the drama. At one point in the picture he jumped up excitedly and, pointing to the screen, exclaimed loudly enough for all to hear, “That’s right! That’s exactly like it was – I know because I was there.!” The scene to which he referred was the one depicting a civil war battle in which he had fought.”

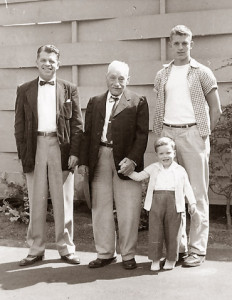

Amos Beach and his great granddaughter Alvis Love, my mother, in 1912, Woodburn, Oregon.

In 1890 Beach applied for a Civil War pension on the basis of an injury suffered during the war. He declared in the application that:

“a horse throwed him while being chased by Mosby’s gang in Luray Valley, Va, in 1863 or 1864 and bruised his right ankle very bad and was doctored by Dr. Sleath at Falmouth, Va, then the 3rd of May 1890 a pile of lumber fell on the same leg breaking it between knee and ankle.” (Invalid Pension)

For this he was awarded a pension of $6 a month, starting in 1890, when he was 48 years old. By the time of his death in 1926 his pension had increased to $65.00 a month.

In his later years he lived in a small house next door to one of his daughters. He loved hunting and fishing. In spite of his war injury, he kept up a vigorous life. When he was 78 years old and camping with his family, he climbed Wauna Point, with an elevation of 3,200 feet. According to a newspaper account, he left his red handkerchief on a staff at the summit, so those at the campground could see it with binoculars, to prove that he had done it. (Civil War Veteran.)

He died at home in 1926, at age 84, of a cerebral hemorrhage, and was buried at Belle Passi Cemetery in Woodburn. The bronze star of the Grand Army of The Republic decorated his tombstone, and commemorates the defining event in his life, the War between the States.

How you are related to Amos Beach

Amos Beach is on your personal Ancestor Fan. He is the grandfather of Alvis Love Whitelaw, and the great grandfather of John, Susan and Nancy Whitelaw.

Sources

Civil War Veteran Who Climbed Wauna Point at Age of 78. The Oregonian, 1 Aug. 1920, Sec. 2, p. 20.

Death Calls Amos Beach (1926) Woodburn Independent, Woodburn, OR

Dunbar, Willis F. 7 May, George S. (1995) Michigan: A History of the Wolverine State. 3rd revised ed. William B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., Grand Rapids, MI, pp. 316-327.

Harvey, Don & Lois, eds. The Michigan Cavalry Brigade. Available on-line at www.michiganinthewar.org/cavalry/michbrig.htm Retrieved: 9/2011.

Invalid Pension Application of Amos Beach, June, 1891. U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

Rosentreter, Roger. (1979). Barry County. Michigan History, Vol. 63, No. 4, pp. 3-7.

Stoller, Gene. (Oct., 1987) Indian fighter really meant business. Woodburn Independent, Woodburn, OR.

Urwin, Gregory J.W.(1990) Custer Victorious. University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln, NB.

U.S. Civil War Soldier Records and Profiles [database on line] Provo, UT. The Generations Network, Inc. 2009.

Whitelaw, Alvis. Interview with Susan Whitelaw, 1985-1993. Portland, Oregon.

Shelley Downs, Beach’s great great great granddaughter at his grave, 1986.

Obituary: Death Calls Amos Beach

Civil War Veteran Succumbs to Attack of Cerebral Hemorrhage. Masonic Funeral Friday.

One of the two remaining Civil War veterans in Woodburn passed away at his home on Settlemeier Avenue at 11:30 a.m. Wednesday, December 22 of cerebral hemorrhage, aged 84 years, 5 months and 24 days. The funeral will be Friday, December 24, at 1:30 p.m. Services will be under the auspices of Woodburn Lodge No. 106, A.F.&A.M., of which he was a charter member. Services will be at Masonic Temple and interment at Belle Passi.

This grand old man and esteemed citizen was born June 28, 1842 near Middleville, Mich., in a log-house, the son of Ashbel and Betsy Beach. He grew up on the farm, going to school in the winter, walking 2 miles there and from in order to get an education. On September 10, 1862, he volunteered in the Michigan Cavalry Brigade as a private under General Custer and at the end of the war he was a sergeant. His Civil War record was as follows:

During the service of the brigade it had been engaged with the enemy at Hanover, Va., June 30, 1863; Hunterstown, Penn., July 2, 1863; Gettysburg, Penn., July 3, 1863; Monterey, Md., July 4, 1863; Cavetown, Md., July 5, 1863; Smithtown, Md., July 6, 1863; Boonsborough, Md., July 6, 1863; Hagerstown, Md., July 6, 1863; Williamsport, Md., July 6, 1863; Boonsborough, Md., July 8, 1863; Hagerstown, Md., July 10, 1863; Williamsport, Md., July 10, 1863; Falling Waters, Md., July 14, 1863; Snicker’s Gap, Va., July 19, 1863; Kelley’s Ford, Va., Sept. 13, 1863; Culpepper Court House, Va., Sept. 14, 1863; Raccoon Ford, Va., Sept. 16, 1863; White’s Ford, Va., Sept. 21, 1863; Jack’s Shop, Va., Sept. 26, 1863; James City, Va., Oct. 9, 10, 1863; Brandy Station, Va., Oct. 11, 1863; Buckland’s Mills, Va., Oct. 19, 1863; Stevensburg, Va., Nov. 19, 1863; Morton’s Ford, Va., Nov. 26, 1863; Richmond, Va., March 1, 1864; Wilderness, Va., May 6, 7, 1864; Beaver Dam Station, Va., May 9, 1864; Yellow Tavern, Va., May 10, 11, 1864; Meadow Bridge, Va., May 12, 1864; Milford, Va., May 27, 1864; Hawe’s Shop, Va., May 28, 1864; Baltimore X Roads, Va., May 29, 1864; Cold Harbor, Va., May 30 and June 1, 1864; Travillian Station, Va., June 11 and 12, 1864; Cold Harbor, Via., July 21, 1864; Winchester, Va., Aug. 11, 1864; Front Royal, Va., August 16, 1864; Leetown, Va., Aug. 25, 1864; Shepardstown, Va., August 25, 1864; Smithfield, Va., Aug. 29, 1864; Berryville, Va., Sept. 3, 1864; Summit, Va., Sept. 4, 1864; Opequan, Va., Sept. 19, 1864; Winchester, Va., Sept. 19, 1864; Luray, Va., Sept. 24, 1864; Port Republic, Va., July 26, 27, 28, 1864; Mount Crawford, VA., Oct. 2, 1864; Woodstock, Va., Oct. 9, 1864; Cedar Creek, Va., Oct. 19, 1864; Madison Court House, Va., Dec. 24, 1864; Louisa Court House, Va., Mar. 8, 1865; Five Forks, Va., Mar. 30, 31, and April 1, 1865; South Side R.R., Va., April 2, 1865; Duck Pond Mills, Va., April 4, 1865; Ridge’s or Sailor’s Creek, Va., April 6, 1865; Appomattox Court House, Va., April 8 and 9, 1865; Willow Springs, Dakota Territory, Aug. 12, 1865.

In addition to the foregoing war record, many incidents in Sergt. Beach’s active career during the conflict between North and South could be given, one being the time when he shot at General Stuart, hitting the hat and cutting the cord and tassel from it, after which he was taken prisoner and held in a bullpen with scarcely anything to eat for 2 weeks and a day, when he made his escape and with the assistance of friendly negroes got through the rebel lines to his own regiment.

After the grand review in Washington following the conclusion of the war he started with comrades for, as he supposed, home, but they were taken down the Ohio river, across plains and mountains to Fort Leavenworth, Fort Laramie and further on, to stop the depredations of the Indians. They were greatly disappointed, not knowing that they were to be used to fight “Injuns”, not finding out the purpose of the movement until they reached St. Louis. It took 38 days to go from Leavenworth to Laramie and they had several fights with the Indian tribes, Sergt. Beach seeing many men, women, and children scalped and killed. He was in this service for six months before being allowed to return home. This extra service was performed after he had been mustered out at Fort Leavenworth, in the fall of 1865.

In 1866 Sergt. Beach married Clara Hatton, an English girl, at Middleville. To this union were born eight children, two of whom, a boy and girl, passed on. The six surviving children are Mrs. Florence Goulet, Mrs. Nettie Zimmerley, Mrs. Mary Whitman, Mrs. Laura Livesay and George Beach, all of Woodburn, and Mrs. Sarah Hardcastle of Salem.

Sergt. Beach came with his children then living to Woodburn, Oregon, in December, 1886, joining his brother Lauriatt here, the latter dying in California not long ago. Later his other brother, John Beach, afterward deceased, came out. Sergt. Beach worked for awhile for J.H. Settlemier in the nurseries and also on farms in the vicinity. When Woodburn was incorporated he was selected marshal and served in that capacity for 26 years, making a most efficient officer. He was also constable and deputy sheriff. He was extremely fond of hunting and fishing. His experiences of the past, especially during the Civil War, are highly interesting. He met President Lincoln on several occasions and shook hands with him more than a dozen times. He never forgot the time he was taken prisoner at Raccoon Ford, Virginia, December 15, 1863, and his daring act in shooting at the rebel, General Stuart of Alabama. (Woodburn Independent, Dec. 1926.)

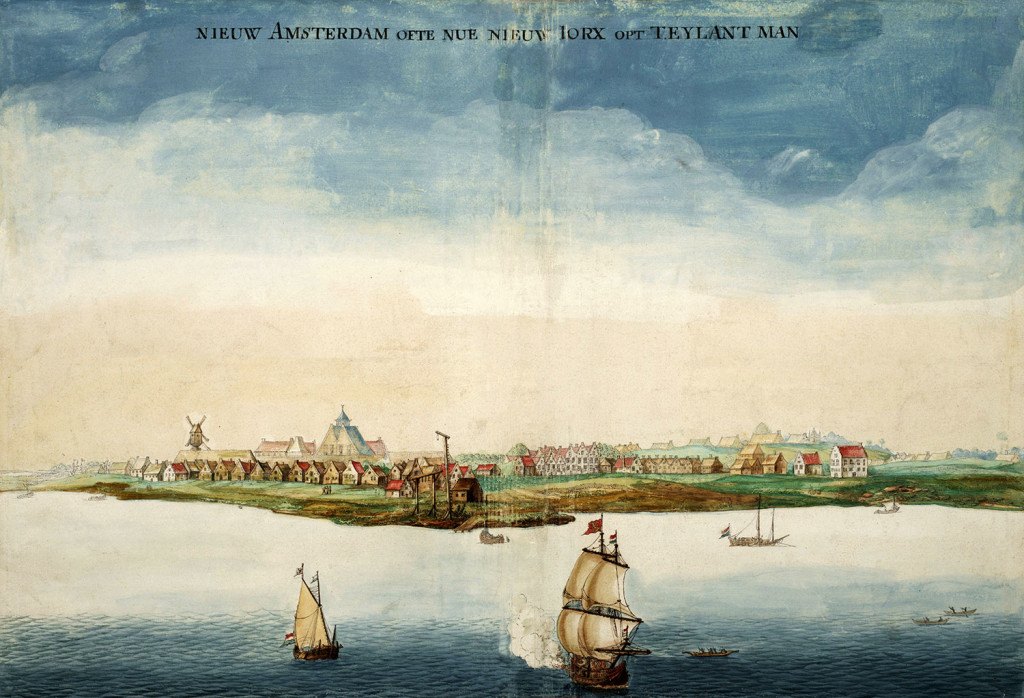

Their destination, Rhode Island colony, had been founded by Roger Williams a century earlier, and was known for its religious toleration and acceptance of a diverse array of immigrants. We don’t know if the Loves chose Rhode Island, or whether they wound up there because the neighboring colonies, Massachusetts and Connecticut, did not want them. Those colonies welcomed only Puritans from England who wanted to live in a theocratic state – in other words, immigrants who were like the people who were already there. The Loves immigrated primarily for economic reasons, not because of religious persecution. But they were no doubt aware that freedom of conscience was the bedrock on which Rhode Island was founded.

Their destination, Rhode Island colony, had been founded by Roger Williams a century earlier, and was known for its religious toleration and acceptance of a diverse array of immigrants. We don’t know if the Loves chose Rhode Island, or whether they wound up there because the neighboring colonies, Massachusetts and Connecticut, did not want them. Those colonies welcomed only Puritans from England who wanted to live in a theocratic state – in other words, immigrants who were like the people who were already there. The Loves immigrated primarily for economic reasons, not because of religious persecution. But they were no doubt aware that freedom of conscience was the bedrock on which Rhode Island was founded.